Exostoses are benign bony growths and, in the equine orthopedic patient, are predominantly found at the palmarolateral/ -medial or plantarolateral/ -medial aspect of the metacarpal/ metatarsal bones. Often the result of stress or injury, not all exostoses are associated with clinical symptoms. However, they should be considered as a cause of lameness.

Guest author Carola Daniel, Lecturer in Large Animal Research Imaging, The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, discusses the use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in assessing bony lesions, and the value of enhanced motion correction technology for improved image quality.

MRI: Its Value in Soft Tissue and Bone Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is well known for its great ability to visualize soft tissues, including tendons and ligaments. This is due the relatively high water content of these structures and water being one of the key components contributing to signal intensity in MR images.

Bone, on the other hand contains only a small amount of tightly bound fluid and is therefore slightly less well-suited to MRI. This is particularly true for very dense cortical bone; cancellous bone however is less dense and more porous and can generate more signal in MR images. Bone injuries such as contusion/ bruising, fractures, or infection (e.g. pedal osteitis or osteomyelitis), are associated with an increase in fluid within the cancellous bone, if they are currently actively inflamed and/ or ongoing bone modelling is present.

This increase in fluid content in active pathology can be visualized on MR images. MRI can therefore be used to help distinguish between currently clinically relevant lesions (fluid signal) and lesions with a more chronic and quiescent character (no/ less fluid signal).

STIR Sequences: Highlighting Active Pathology

Short Tau Inversion Recovery (STIR) is the MR sequence best suited to assess these kind of bone lesions and their current “activity”. The technique suppresses the signal of fat and enhances the contrast of regions with increased fluid content (e.g. edema, inflammation/ infection). However, the specific machine settings required for STIR images (short inversion time) make them susceptible to motion artifact. This is further exacerbated by the relatively long acquisition time for these images, which requires the patient to be very still over a long period.

The Challenge of Motion Artefact in Standing MRI

In standing MRI of the equine patient, this can usually be achieved for images of the distal limb. However, images from the level of the fetlock and further proximal are often heavily affected by motion artifact due to slight swaying of the sedated patient. Therefore, image quality of STIR sequences is usually best in the distal limb (foot and pastern), where very little motion artifact occurs.

However, since the recent introduction of modern motion correction software, image quality for the more proximal limb has increased significantly and good diagnostic images can be achieved.

For example, iNAV is the latest motion correction software developed by Hallmarq Veterinary Imaging. Designed to measure the position of the horse’s leg in real time, it significantly reduces the impact of limb movement during image acquisition and helps maintain diagnostic integrity. Whether imaging the fetlock, tarsus, carpus, or high suspensory, iNAV preserves the detail and clarity required for accurate assessments.

Exostoses: Understanding the Lesions Behind the Lameness

Exostoses are benign bony growths. In the orthopaedic equine patient exostoses are predominantly found at the palmarolateral/ -medial or plantarolateral/ -medial aspect of the metacarpal/ metatarsal bones and are often the result of stress or injury to the interosseous ligament between the second or fourth and third metacarpal/ metatarsal bone (“true splint”) or direct bony trauma (“false splint”).

While not all equine exostoses are associated with clinical symptoms, they should be considered as a cause of lameness (Bertoni et al., 2012). MR imaging can help to determine the current level of active modelling and inflammation, as well as further underlying causes and assist with assessment of secondary problems such as impingement of the suspensory ligament and resulting desmopathy.

As these lesions are usually located proximal to the fetlock, motion correction is beneficial to achieve diagnostic image quality.

Case 1: Metacarpal Exostosis Without Ligament Involvement

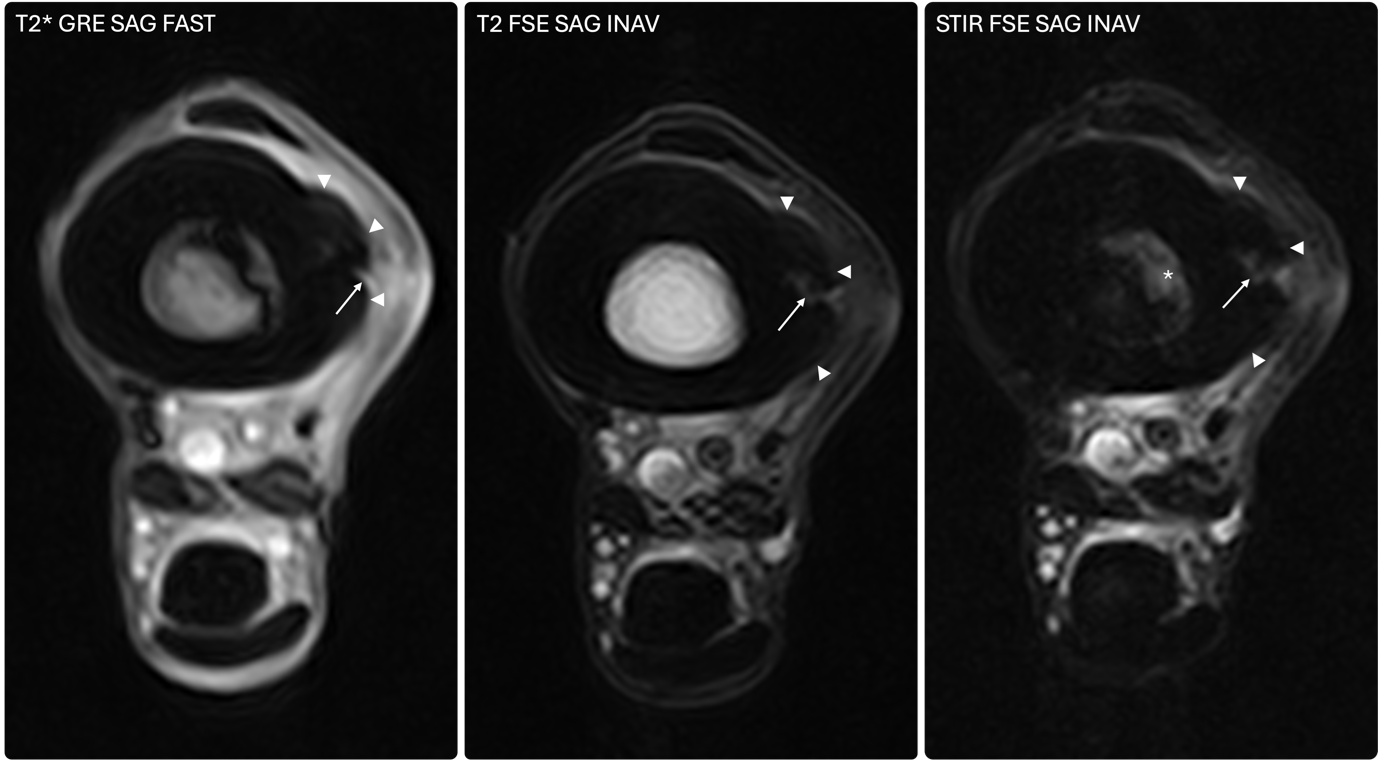

A 9-year-old Thoroughbred gelding presented with an exostosis at the proximal third of the second metacarpal bone. MR imaging confirmed periosteal reaction with concurrent increased signal in all sequence types, including STIR sequences (Fig.1). This is indicative of poorly organized new bone formation and active remodeling and inflammation, in this case likely secondary to focal trauma to the periosteum. At this stage, no MR evidence of concurrent desmopathy of the suspensory ligament was evident.

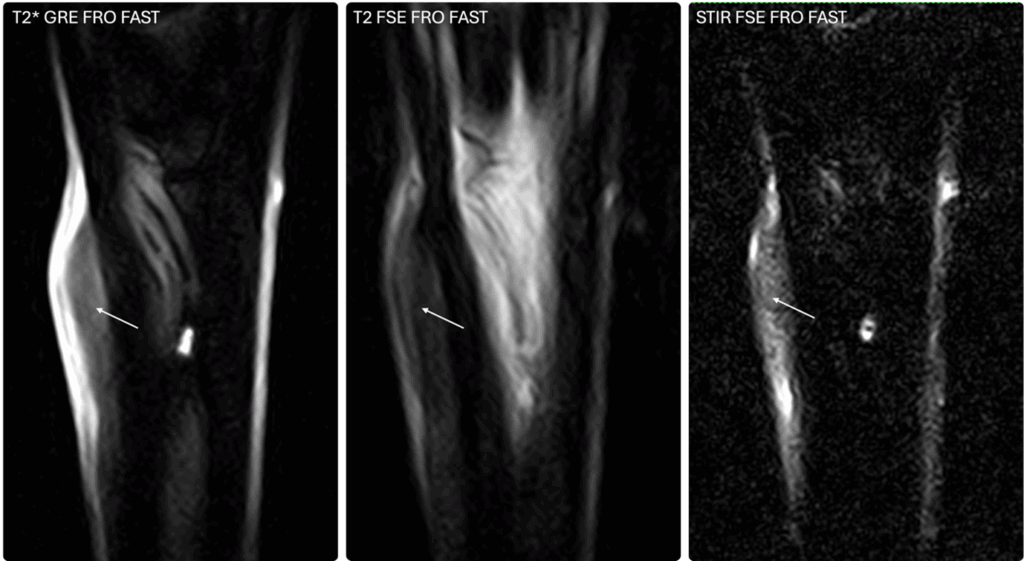

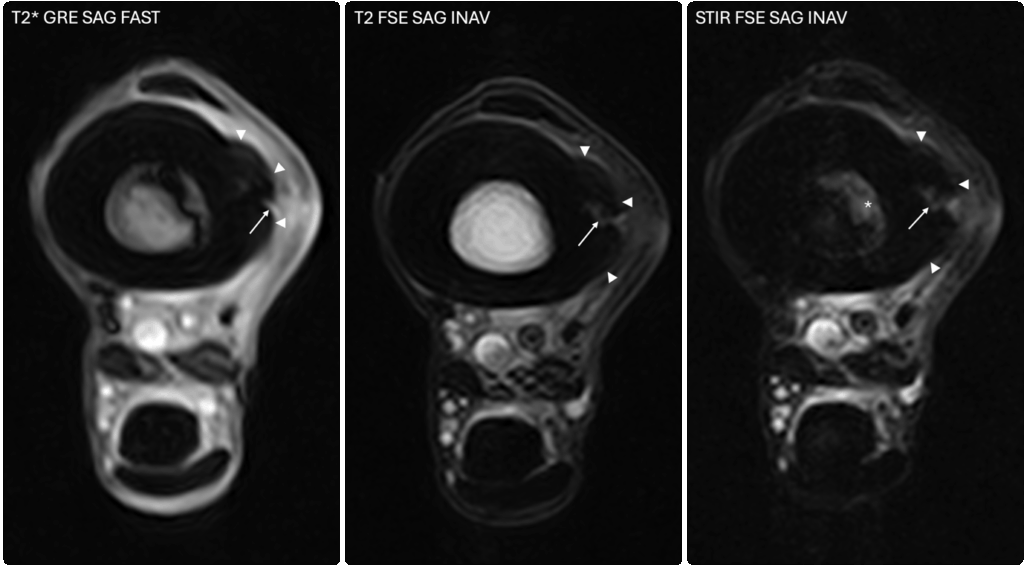

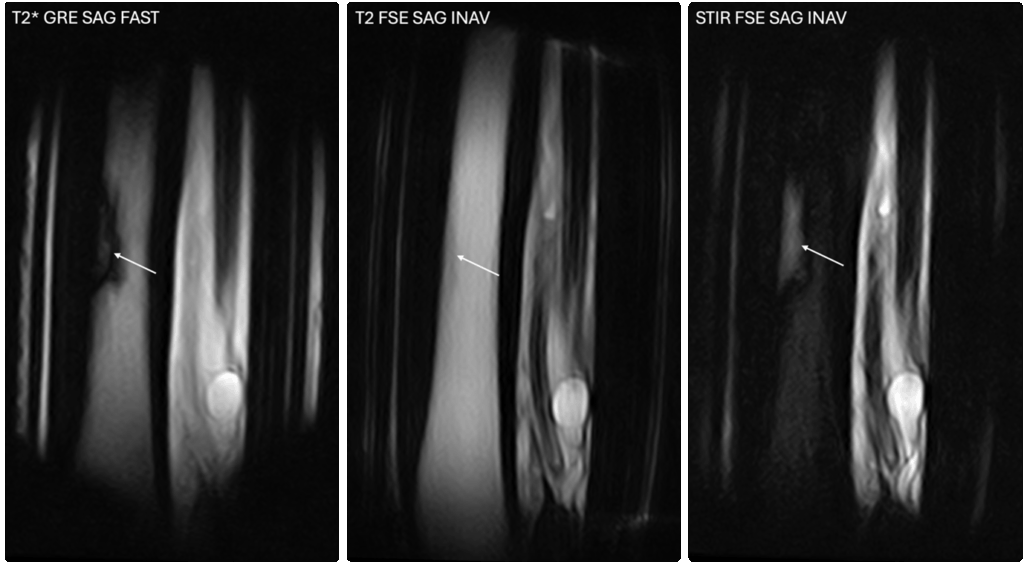

Case 2: Metatarsal Exostosis With Underlying Infection

A 7-year-old Thoroughbred gelding presented with an exostosis at the lateral aspect of the third metatarsal bone and lameness of the ipsilateral limb. The lameness was abolished following a low-6-point nerve block. MR images showed a large, irregularly marginated periosteal reaction with increased signal intensity in all sequence types (including STIR, Fig.2). A hyperintense line extended from the cortical bone into the medulla (Fig.2), which also showed a region of increased STIR signal (Fig.2 and Fig.3).

These findings were indicative of active modeling of the exostosis and marked inflammation or infection likely spreading into the underlying medulla. Surgical curettage confirmed a sequestrum as the underlying cause.

Conclusion

MR imaging can add value to assessing bony lesions such as equine exostoses, particularly where active modelling, inflammation or infection needs to be assessed. New motion correction technology improves image quality and aids MR assessment of more patients.