Pareidolia is the perception of a meaningful image in an otherwise ambiguous visual pattern. For many of us, finding shapes in MRI images is simply a matter of whimsy as we find animals or smiling faces within an inanimate object. Guest author, Rose Krupka Peters, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology) writes for us on the fascinating subject of Pareidolia and considers its use in helping to train the novice veterinary student in rapid MRI assessments.

What is Pareidolia?

Pareidolia is the perception of a meaningful image in an otherwise ambiguous visual pattern. When we see shapes in the clouds or faces smiling from an inanimate object, we are experiencing the phenomenon of pareidolia.

Humans have developed an active processing center in the temporal lobe of the brain, termed the fusiform face area (FFA), that allows us to process a large amount of facial visual information quickly.1,2 This is important for social animals who must rapidly understand identity, emotions, and intent from a glance. When there is a lesion in the right FFA, humans can experience a phenomenon called “face blindness” in which it is very difficult to identify faces, even of people we see every day.

The famed neuroscientist and author, Oliver Sacks, suffered from this condition and shared his perspective in the 2010 Radiolab episode “Strangers in the Mirror.”

The FFA is also very active when humans are shown inanimate objects that resemble faces. This phenomenon has sparked whimsical social communities through platforms like:

Instagram: @facespics

Instagram: @radiologypareidolia

Reddit: r/Pareidolia

You may be able to look around you and find something that you can imagine to be a face, like this latch on an exam room door (Fig 2) that seems happy to see us!

How does the Pareidolia Phenomenon help us learn pattern recognition in radiology?

The FFA is not only active when recognizing faces but also appears to be involved with recognizing familiar shapes in other circumstances. For example, the FFA helps an experienced birder to recognize the identity of a bird hidden in the foliage much more quickly and accurately than a novice.

Radiology is centered on the art of being able to rapidly distinguish visually abnormal from normal shapes and patterns. Like any skill, practice enhances our accuracy and speed at performing this task. The FFA becomes more active and developed as an individual becomes more expert at identifying certain patterns. In developing these skills, it appears that capitalizing on an inherent predilection toward faces and other familiar objects can improve our ability to recognize important shapes in otherwise ambiguous patterns.

This can be utilized as a teaching method to improve diagnostic accuracy in the inexperienced radiologist. When we can assign a familiar shape to a piece of anatomy or an indicator of pathology, then the student may be able to make a more memorable association for quicker recognition later.3,6 Using pareidolia to enhance diagnostic accuracy in MRI can involve using shapes to identify normal anatomy, recognize pathology, and sometimes may simply be a whimsical observation.

Pareidolia in veterinary MRI

Shapes indicating ‘normal’

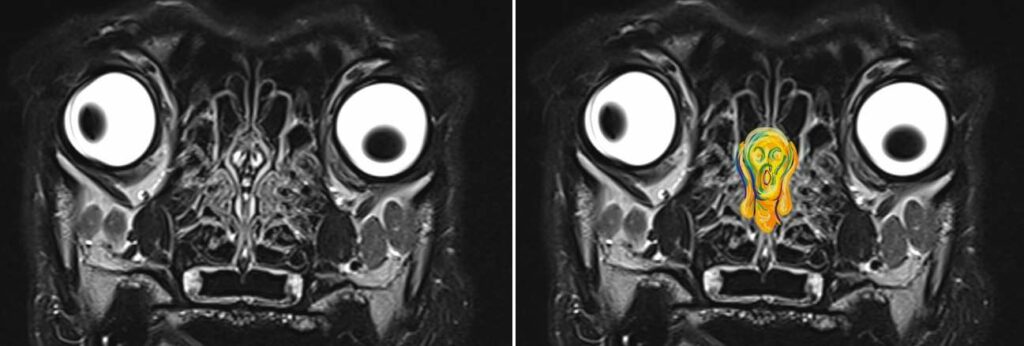

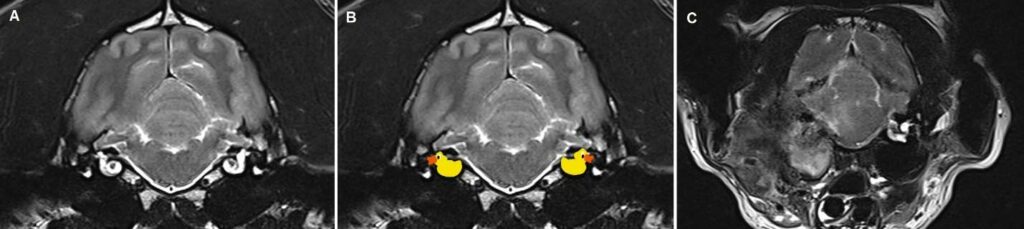

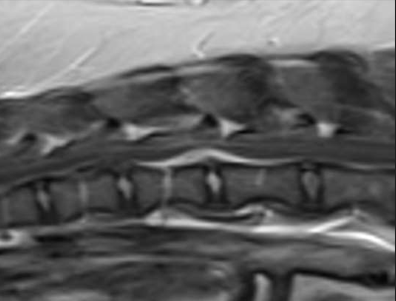

Swimming ducks

Many of you may be familiar with the “swimming ducks” seen on transverse T2-weighted views of the canine and feline head (Fig 3). These represent perilymph within the semicircular canals and cochlea and may be more difficult to see in cases with otitis interna. Notice how well we can see both cochlea in the normal animal (A), but this shape is obliterated in this patient with severe otitis associated with external mass effect, osteomyelitis, and inflammatory extension into the brain (C).

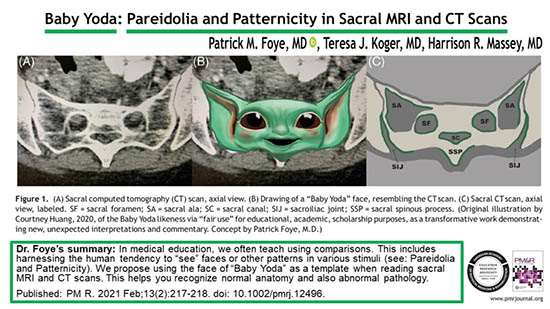

Baby Yoda

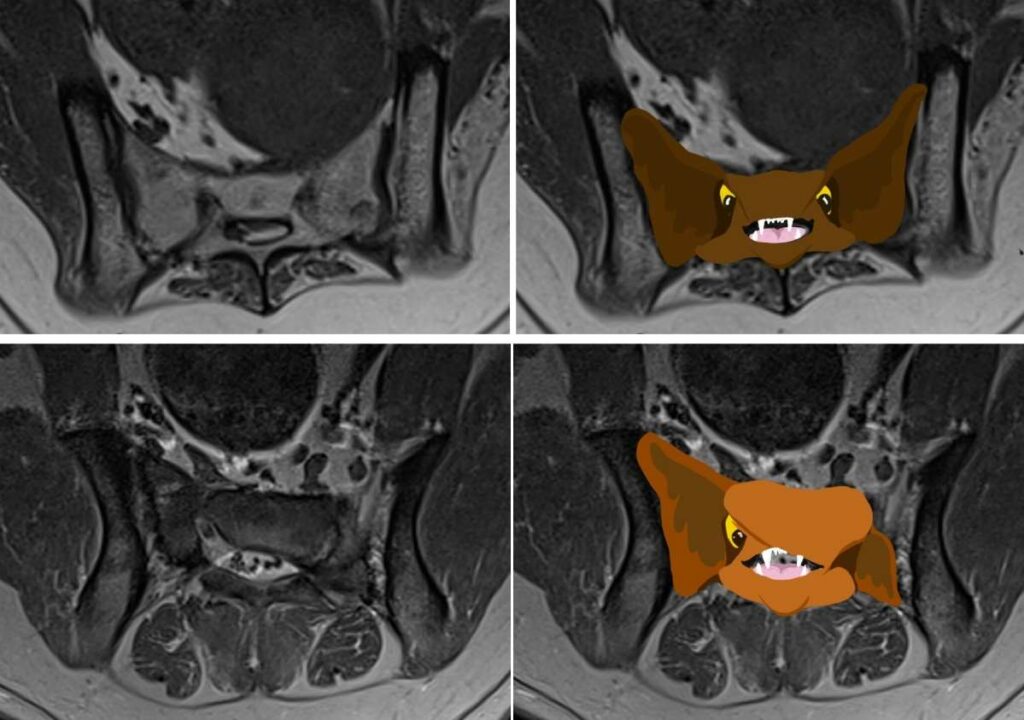

The smiling face of Baby Yoda (Fig 4) has been proposed as a tool for teaching medical students to recognize normal sacral features on MRI and CT imaging.4

We may be able to apply similar principles to the canine sacrum, though the anatomical diversity may make us have to consider other faces like this whimsical creature (Fig 5).

Can you see how this helps us to better recognize the sacral bone malformation in the second patient? (Fig 6 below)

Shapes indicating ‘abnormal’

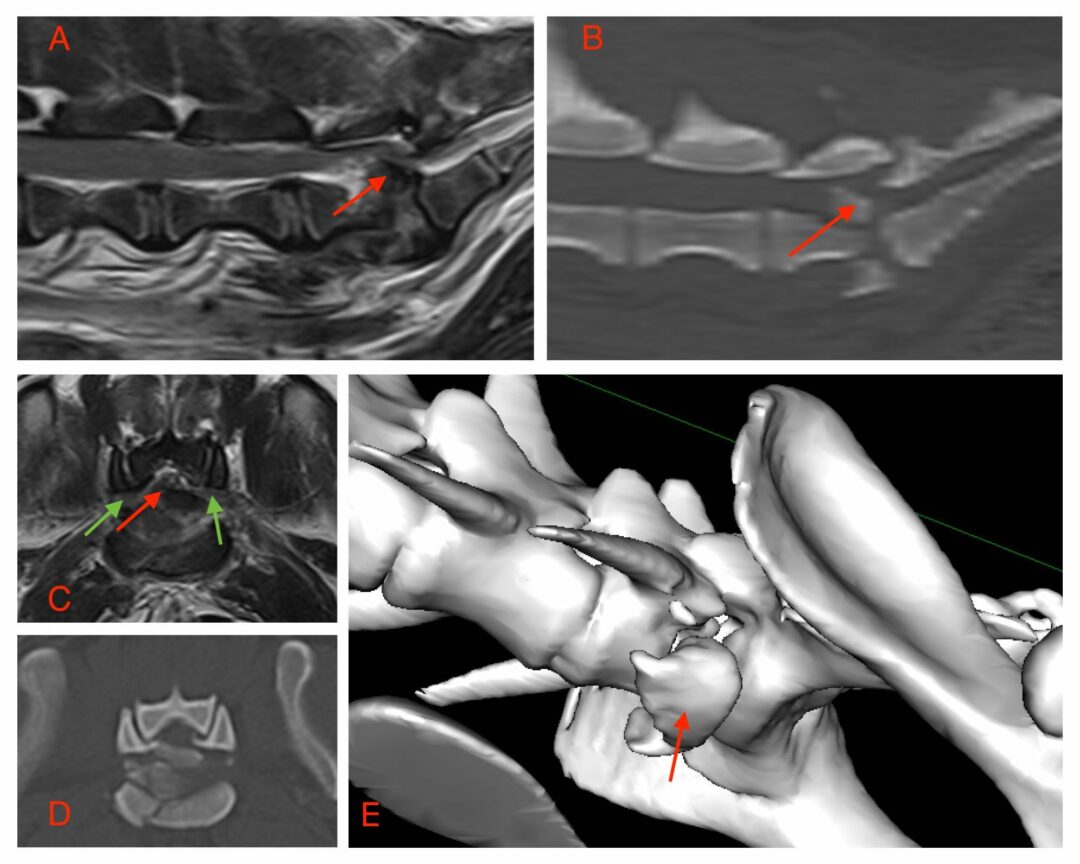

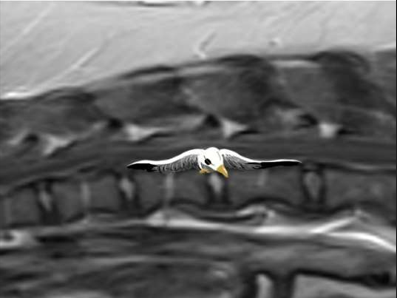

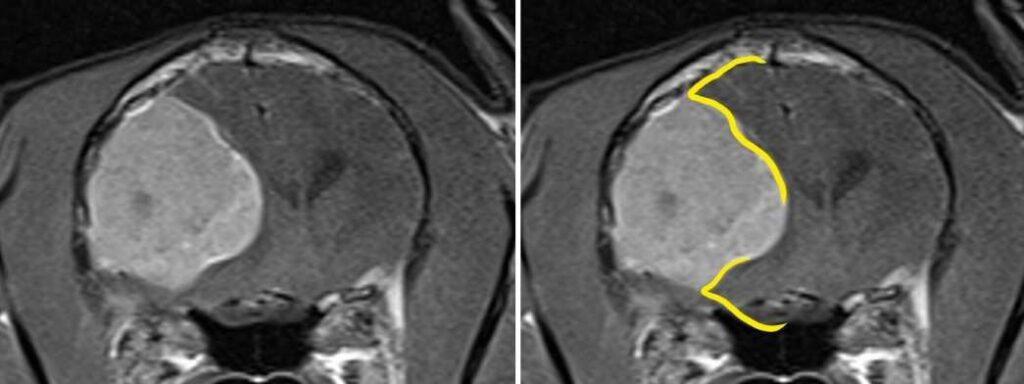

Gull wing sign

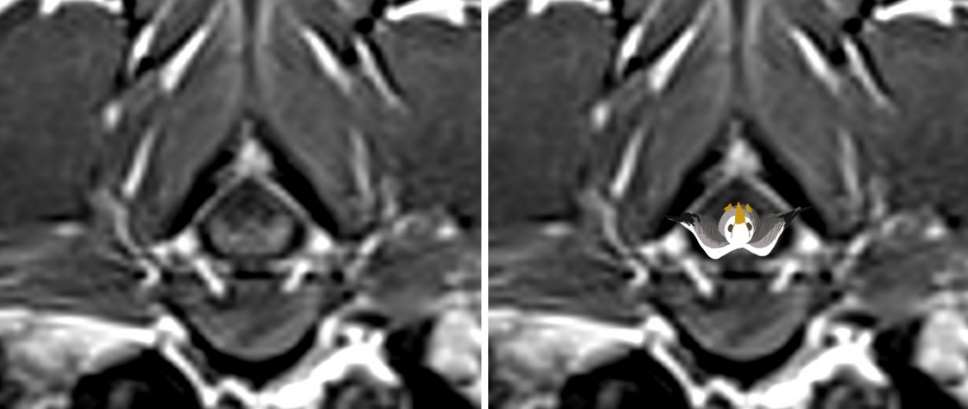

A ventral bi-lobed extradural mass effect on transverse imaging of the spinal cord suggests a greater likelihood of round cell neoplasia according to this recent publication by Monto et al7. In these cases, I like to imagine the gull flying upside down. The axial example below (Fig 7) is from a pet with suspected lymphosarcoma.

Alternatively, we might think think of a “gull-sign” when looking at sagittal views (Fig. 8 a and b) of cases with hydrated nucleus pulposus extrusion (HNPE)

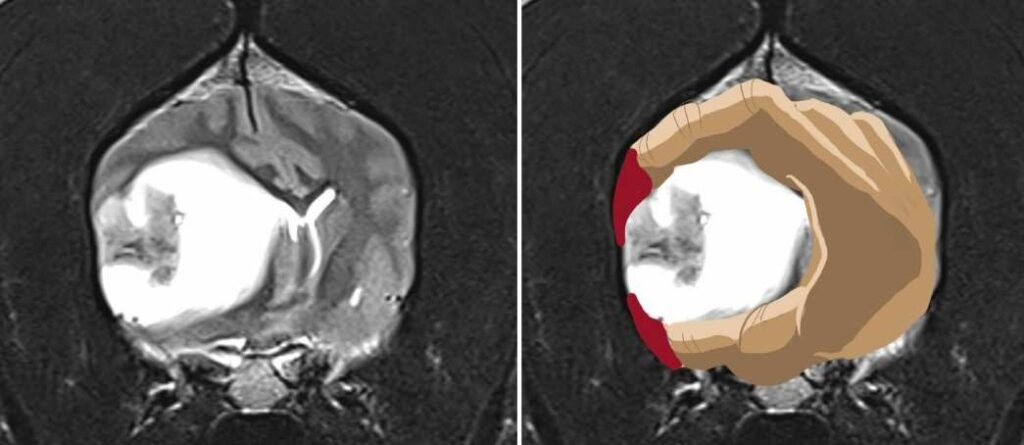

Claw sign

A peripherally located expansile mass that thins the adjacent parenchyma to an acute angle can help to differentiate a glial cell tumor from a meningioma (Fig. 9) according to this publication by Glamann et al.5

You can see the difference when comparing to a similarly-positioned meningioma tumor where the longer, tapered, claw-like appearance (Fig. 10) of the adjacent cortical tissue is absent:

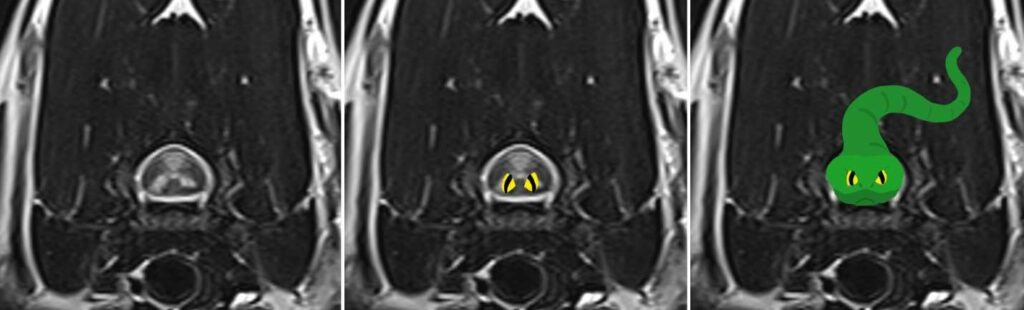

Snake eye Myelopathy

Bilaterally symmetric spinal cord lesions of various causes have been found in cervical spinal cord transverse images (Fig. 11) and can be an indicator of prognosis for return to function according to this publication by Rossmeisl et al.8

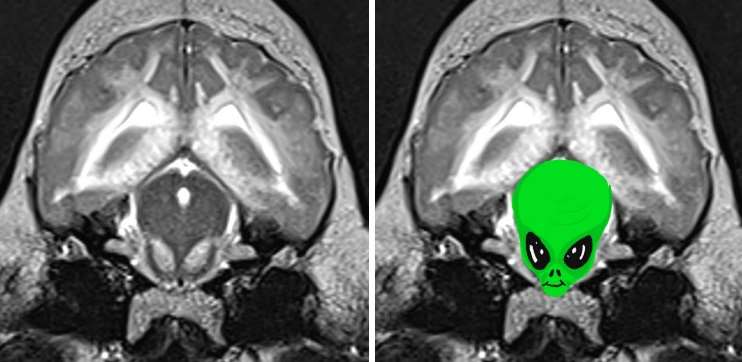

Shapes that don’t add or detract to the diagnostic process: incidental amusement

For many of us, finding shapes in MRI images is simply a matter of whimsy as we find animals or smiling faces. However, perhaps we can collectively channel this whimsical inclination into a practical shape-based guide to train the novice veterinary student in rapid MRI assessments.

These remarkable symmetrical lesions in a dog with suspected bromethalin toxicity (Fig. 11) makes the midbrain look like an alien.

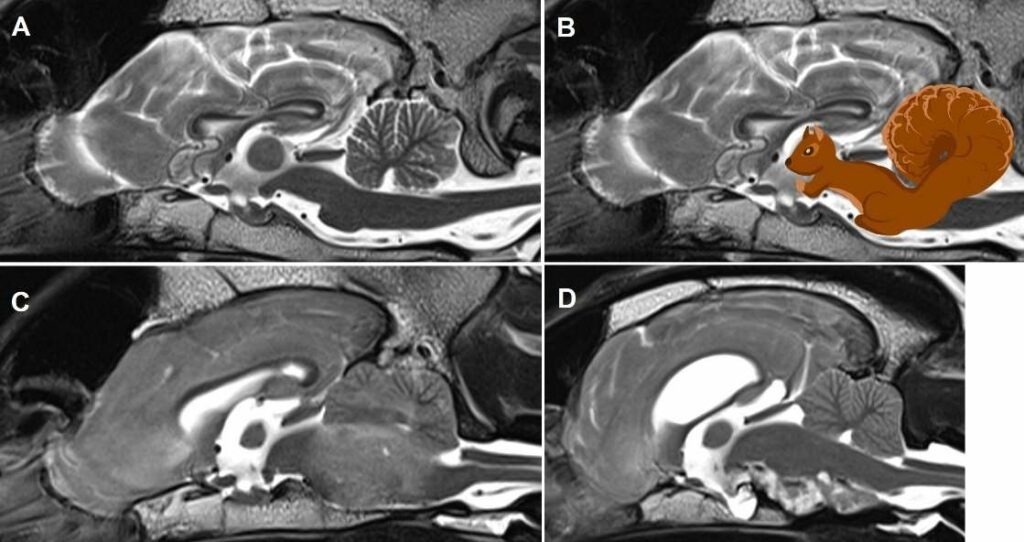

Have you ever noticed that the sagittal view of the brainstem and cerebellum looks like a squirrel with a fluffy tail? Watch out for anything that seems to make that “squirrel” shape more difficult to appreciate like the peritumoral edema in C and the ventral extramedullary lesion in D (Fig.12)

So is Pareidolia pure whimsy or a valuable teaching aid? The answer is, of course, subjective but, if you have favorite hidden pictures in veterinary MRI imaging, please feel free to share them with us!

References

- Akdeniz G, Toker S, Atil I. Neural mechanisms underlying visual pareidolia processing: an fMRI study. Pak J Med Sci. 2018; Nov-Dec;34(6):1560-1566.

- Bilalic M. Revisiting the role of the fusiform face area in expertise. J Cogn Neurosci. 2016; Sep;28(9):1345-57.

- Fatehi D, Salehi M, Farshchian N, et al. Pareidolia as additional approach to improving education and learning in neuroradiology; new cases and literature review. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2016; 9(1).

- Foye P, Koger T, Massey H. Baby Yoda : Pareidolia and Patternicity in Sacral MRI and CT Scan. PM&R. 2021; Feb; 13(2):217-218.

- Glamann S, Jeffery N, Levine J, et al. The “Claw Sign” may aid in axial localization in cases of peripherally located canine glioma on MRI. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2023; 64:706-712.

- Kok E, Sorger B, Geel K, et al. Holistic processing only? The role of the right fusiform face area in radiological expertise. PLoS One. 2021; Sep 1; 16(9):e0256849.

- Monto T, Hecht S, Auger M, Springer C. A “gullwing sign” on magnetic resonance imaging of extradural spinal tumors in dogs and cats allows prioritization of round cell neoplasia. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2024; 65:832-835.

- Rossmeisl Jr J, Cecere T, Kortz G, et al. Canine Snake-Eye Myelopathy : Clinical, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Pathologic Findings in Four Cases. Front Vet Sci. 2019; Vol. 6.