When faced with a neurological case, every clue matters. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) collection is often considered a key diagnostic step, offering insight into conditions ranging from infectious and immune-mediated diseases to neoplasia. But is a spinal tap always the right choice?

In this article, Cecilia Danciu, DVM MVetMed PhD DipECVN MRCVS, Lecturer in Veterinary Neurology at the University of Liverpool’s Small Animal Teaching Hospital, explores the role of CSF analysis in veterinary neurology, outlining when it can be invaluable, how it’s performed, and the risks clinicians need to weigh before proceeding.

What is the cerebrospinal fluid?

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a plasma ultrafiltrate, that surrounds the brain, the spinal cord and fills the ventricular system of the brain. It offers physical support of the neural structures, aids in intracerebral transportation, excretion, and control of the chemical environment of the central nervous system (CNS).

Where is the CSF produced?

Most of the CSF is produced in the choroid plexus of the third and fourth ventricles, then in a lesser extent in the pia-arachnoid vessels, ependymal lining of the ventricles and in the CNS parenchyma.

Where is the CSF absorbed?

The CSF has a predominantly caudal flow, and it gets absorbed in the arachnoid villi, cerebral veins and the in the lymphatic vessels of the cranial and spinal nerves.

Why do we want to collect CSF?

In order to reach a definitive neurological diagnosis, histopathology is required. Taking biopsies of the CNS is invasive and associated with risks. However, performing spinal tap to collect CSF, generally, is considered a relatively safe and non-invasive procedure and can give information on the presence of pathology within the CNS:

- infectious: i.e., protozoal, fungal, bacterial meningoencephalitides

- non-infectious inflammatory: i.e., immune-mediated meningoencephalitides (meningoencephalitis of unknown aetiology, steroid-responsive meningitis-arteritis)

- and neoplastic processes: i.e., round cell tumours such as lymphoma or histiocytic sarcoma

Despite this, presence of changes in the CSF does not correlate with the severity of the lesion. Additionally, absence of CSF changes does not rule out inflammatory or neoplastic disease.

How is the CSF collected?

The decision to proceed with CSF collection is based on the evaluation of clinical and imaging findings, alongside careful consideration of the likely diagnostic yield and overall risk–benefit for the individual patient. The collection of CSF is always performed by a trained veterinarian after a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan, to interpret findings and to aid in decision making.

The CSF is collected under general anaesthesia using an aseptic technique. Because, the CSF has a predominant caudal flow, the aim is to collect caudally to the lesion. An exception to this can be a cervical lesion, where a tap performed in the cerebellomedullary cistern may be of a higher yield. The two locations for the CSF collection would include:

- The cerebellomedullary cistern which is located in the dorsal subarachnoid space at the level of the first two cervical vertebrae (atlas and axis)

- The lumbar subarachnoid space

For the latter, the CSF collection is performed between L5-L6 in dogs and L6-L7 in cats. A 22 or 20-gauge, 1.5-inch spinal needle will usually reach the subarachnoid space in most dogs and cats. The maximum CSF that can be collected is approximately 1 ml/5 Kg body weight, all by gravitational drop through the spinal needle. The CSF can be collected in plain collection tubes for quantitative analysis, which would include total nucleated cell count, red blood cell count, protein concentration and cytological analysis. The analysis is aimed to be performed within 30 minutes to one hour from collection. Additional testing can be performed (collected in EDTA tubes for ELISA, PCR and biomarkers) as required.

Is it always safe to collect CSF?

It is not always safe to collect CSF!

One contraindication would include the patient being unstable under general anaesthesia. In this scenario, prioritizing patient stability and potentially rescheduling the CSF collection is advisable. Evidence of coagulopathy is another contraindication, as this can result in the development of subcutaneous, epidural or subarachnoid bleeding.

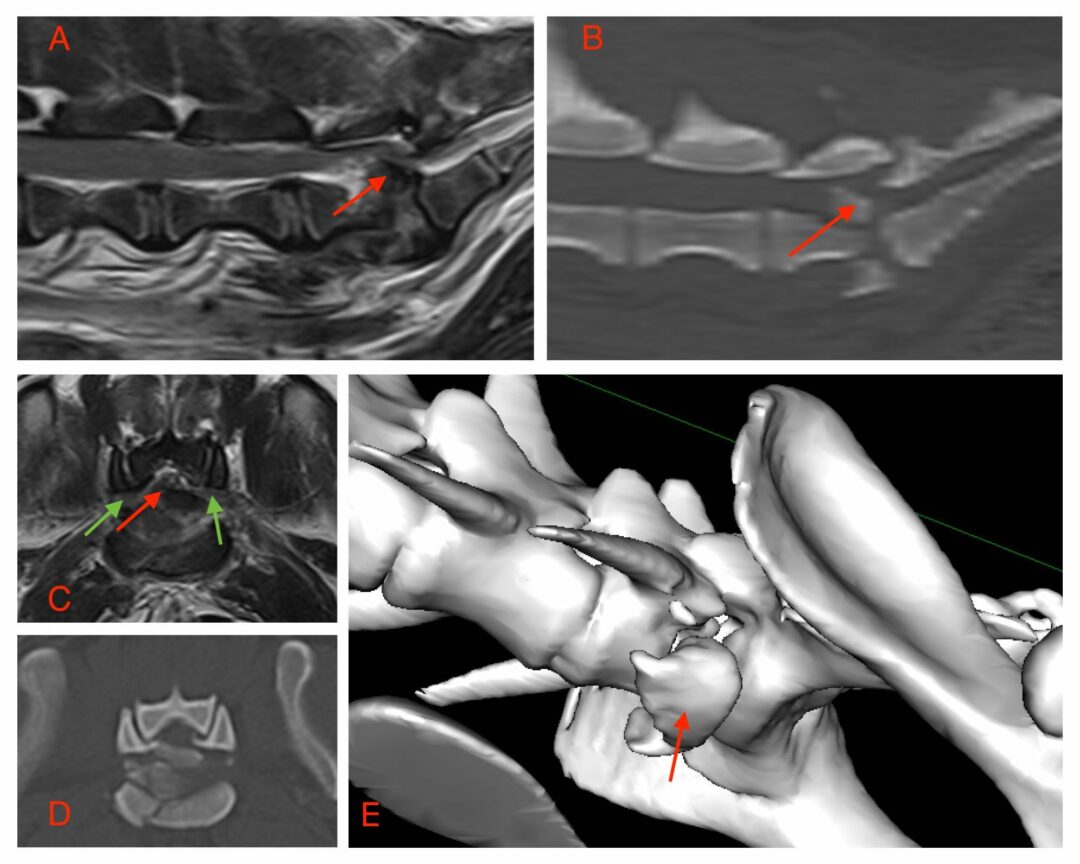

Another contraindication would include suspected or confirmed instability affecting the vertebral column (i.e., atanto-axial instability, or fracture/luxation). Collection of CSF is contraindicated if there is evidence of increased intracranial pressure, that could potentially result in transtentorial or foramen magnum herniation (Figure 1).

Another reason why CSF collection could be contraindicated includes pyoderma at the site of needle placement, because this way infectious agents could be introduced in the subarachnoid space or CNS.

Which complications have been associated with CSF collection in dogs?

Minor complications associated with CSF collection have been reported in dogs and include the development of a subcutaneous hematoma in approximately 1%, local dermatitis in approximately 0.6%, or the inability to collect CSF in 7.8% when performed in veterinary referral practice.

More severe complications have been infrequently reported in single case reports, including progressive myelomalacia and hematomyelia after lumbar CSF collection in dogs.

The importance of CSF studies

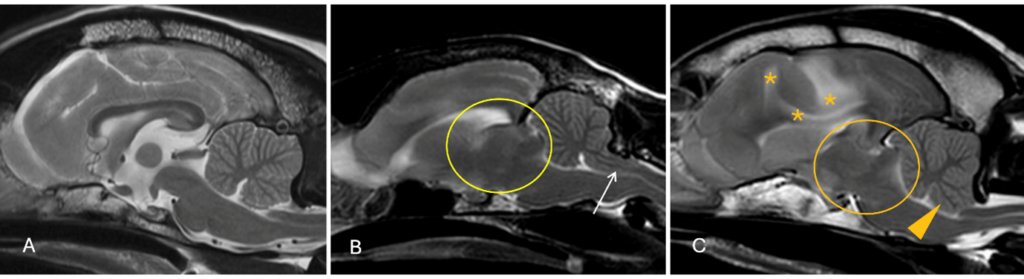

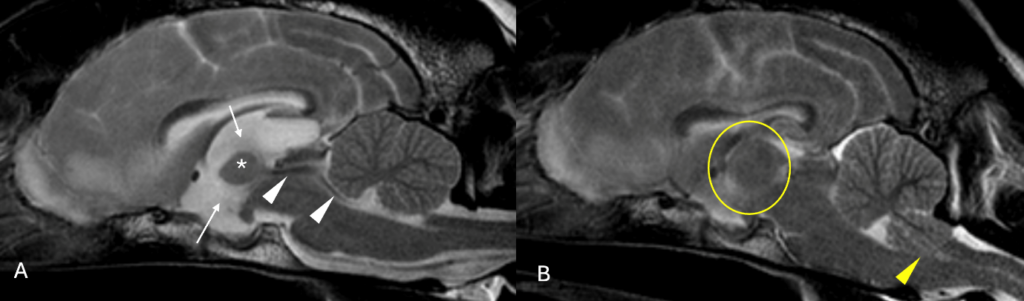

In a larger study, 0.15% of dogs experienced a major complication from over 7000 CSF collections performed in a veterinary referral practice setting. Complications included cardiopulmonary arrest or severe neurological deterioration leading to death or euthanasia. Clinical signs that were more commonly picked up in these dogs, included obtundation and multifocal neuroanatomical localisation. Changes that were observed on the MRI studies before the CSF collection, included effacement of the cerebral sulci suggesting expansion of brain parenchyma and dilatation of the ventricular system, suggesting increased intraventricular pressure. Repeat MRI after the complication could aid in understanding in the reason of deterioration (Figure 2).

CSF collection: key takeaways

The frequency of complications following CSF collection remain low, but when it occurs, the mortality rate can be high. Therefore, prior MRI scan and careful individual evaluation of each patient is indicated, to reduce the risks associated with CSF collection in dogs.

References

- Danciu CG, McCarthy A, Crawford A. Major Complications Associated With Cerebrospinal Fluid Collection in 11 Dogs: Clinical Presentation and Imaging Characteristics. J Vet Intern Med. 2025 Jul-Aug;39(4):e70165.

- Fentem R, Nagendran A, Marioni-Henry K, Madden M, Phillipps S, Cooper C, Gonçalves R. Complications associated with cerebrospinal fluid collection in dogs. Vet Rec. 2023 Sep 20;193(6):e2787.

- Danciu CG, Szladovits B, Crawford AH, Ognean L, De Decker S. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis lacks diagnostic specificity in dogs with vestibular disease. Vet Rec. 2021 Nov;189(10):e557.

- Cook L, Drost WT. Hemorrhagic Myelomalacia in a Bichon Frise Following Lumbar Spinal Tap-A Case Report. Top Companion Anim Med. 2019 Mar;34:47-50.

- Di Terlizzi R, Platt SR. The function, composition and analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in companion animals: part II – analysis. Vet J. 2009 Apr;180(1):15-32.

- Luján Feliu-Pascual A, Garosi L, Dennis R, Platt S. Iatrogenic brainstem injury during cerebellomedullary cistern puncture. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2008 Sep-Oct;49(5):467-71.

- Platt SR, Dennis R, Murphy K, De Stefani A. Hematomyelia secondary to lumbar cerebrospinal fluid acquisition in a dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005 Nov-Dec;46(6):467-71.