MRI has become the imaging tool of choice for diagnosing a stroke* or vascular event in dogs. It allows vets to confirm the stroke, determine its type, and even estimate the dog’s age based on the characteristics of the MRI. Guest author Ryan Gibson, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology) – also known as The Brain Dogtor (@thebraindogtor) – dives into the similarities and differences between strokes in dogs and humans, the types of strokes that dogs suffer, the vital role that MRI plays in diagnosing canine stroke, and the likely prognosis in each case. It makes for a fascinating read.

*Note: The author elected to use the term “stroke” to better align with the terminology used in human medicine to help with pet owner comprehension. The aim is that this will aid comprehension among readers and allow for a better understanding of how this condition differs between dogs and humans.

Intracranial strokes in dogs: similar, yet different to humans

Strokes in dogs can also be referred to as a vascular event, a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), or an infarct. Stokes result from a sudden interruption of blood supply to any part of the brain. When the blood flow is cut off from the brain, the brain cells (neurons) are deprived of oxygen and nutrients, leading to loss of function or even cell death in the part of the brain fed by that vessel. Interestingly, strokes used to be considered uncommon in dogs, with one study finding they make up only around 1–2% of neurological cases at referral clinics. However, this study was likely prone to bias due to underrepresented populations that may not have sought out referrals or improved before they could be seen. With advanced imaging like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and improved access to these MRI machines, veterinary neurologists recognize strokes in pets more frequently than before.

Corticospinal or rubrospinal?

When there is a lack of blood flow to the brain, there is often a rapid onset of neurological signs consistent with the affected part of the brain. For example, a stroke of the occipital cortex, which interprets vision, may lead to vision loss. In contrast, a stroke to the cerebellum (which helps with the coordination of movements) may lead to gait, balance, or other issues. It is essential to recognize that dogs and humans don’t necessarily have the same clinical signs when they have a stroke. Humans use a lot of our cerebrum, the largest part of the brain. It is involved in motor planning and gait development, with our primary motor track, the corticospinal tract, originating from this part of our brain. In comparison, dogs use more of their brainstem to generate their gait, with their primary motor tract, the rubrospinal tract, originating from here. For this reason, a stroke in their cortex does not often lead to facial or limb weakness on the opposite side of the body, which we see as a common sign in humans.

Know the signs of a canine stroke

Clinical signs of a stroke in dogs may include walking in circles, knuckling over in the paw due to a lack of being unable to tell where the limb is in relation to their body, head tilt, loss of balance and coordination, blindness, changes in gait, and even nerve dysfunction to the face. The clinical signs seen are highly associated with the part of the brain that is affected. Depending on the underlying cause and location, some clinical signs may be mild, while others may be severe. Often, a stroke/vascular event can occur and show worsening signs within the first 24 to 48 hours. After this time, their clinical signs stay the same or improve unless a second vascular event occurs.

Strokes are not the only cause of these clinical signs; we will talk about differentiating between strokes and other neurological conditions below.

Types of strokes in dogs: ischemic vs. hemorrhagic

Ischemic stroke

An ischemic stroke occurs when a vessel supplying the brain becomes blocked, usually by a blood clot or other material, cutting off blood flow to part of the brain. This is the most common type of stroke in dogs. This type of stroke can occur secondary to underlying diseases such as those that make an animal more prone to clots, such as Cushing’s Disease (Hyperadrenocorticism), kidney disease, hypothyroidism, blood pressure, or heart disease. However, even with extensive work up about half the time, no concurrent or underlying cause is identified.

Haemorrhagic stroke

A haemorrhagic stroke happens when a blood vessel ruptures and bleeds into or around the brain, causing damage to brain tissues and increased pressure inside the skull. Bleeding can occur within the brain tissue or in the spaces surrounding the brain, depending on the vessel involved. Dogs rarely get bleeding between the tissue covering the brain and the skull (extradural haemorrhage), so emergently drilling a hole into a dog’s skull, as seen in many medical dramas on TV, has a much more limited function in veterinary species. That does not mean surgery is not warranted, just that we usually need a much larger hole and more invasive procedure to get to deeper levels. Just like in ischemic strokes, multiple underlying conditions can lead to this occurring, including clotting disorders, eating some forms of rat poison, or bleeding of another lesion, such as a brain tumuor. In some cases, the bleeding may not have an underlying or identified cause, and we call this idiopathic. Compared to humans, aneurysms and the clipping of aneurysms are rare and mainly reported only in research settings.

Diagnosing canine stroke: the role of MRI

If a stroke has occurred, the MRI will typically show an area of abnormal tissue in the brain. For example, in an ischemic stroke (where blood flow is blocked), a sharply demarcated brain region may appear brighter or different on specific MRI sequences, corresponding to the infarcted (affected) tissue where water is no longer moving around. In a haemorrhagic stroke (bleeding event), the MRI will show the presence of blood; acute bleeding often has a distinct appearance on the MRI. Interestingly, the time the bleeding starts and the time the dog is being imaged can change a blood clot’s imaging pattern/findings. Thus, medical history should always be considered a vital component.

In short, an MRI can usually tell us not only that a stroke occurred but also whether it was due to a blockage or a bleed by how the lesion looks on the scan. In comparison, a CT scan can often identify haemorrhagic bleeds but does not have the same sensitivity as an MRI to identify ischemic bleeds.”

Ryan Gibson, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)

Another reason MRI is so helpful is that it helps rule out other problems. As noted, the signs of a stroke are associated more with the location than the underlying disease. The MRI scan will reveal if there is any evidence of a different brain issue that could have caused the sudden signs, such as a brain tumour, inflammatory process (encephalitis), or, in some cases, bleeding associated with one of these underlying causes.

The benefits of repeat MRI

Often, if the MRI shows a lesion in the brain consistent with a stroke, through a series of sequences including Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) sequences, a preliminary diagnosis can be made. Many veterinary neurologists will collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid via a spinal tap under the same anaesthesia event to check for inflammation that did not appear on the MRI to fully evaluate and further support the diagnosis. This is significantly more likely to occur in the case of an ischemic stroke as some causes of haemorrhagic strokes or increased pressure inside the skull may increase the risk of performing a CSF tap. Normal spinal fluid alongside a lesion characteristic of a stroke on MRI strongly supports a stroke/vascular event. In some cases, however, repeat imaging may be required to fully corroborate the diagnosis in a living animal, especially if mild abnormalities are noted on the CSF analysis.

MRI has become the imaging tool of choice for diagnosing a stroke or vascular event in dogs. It allows vets to confirm the stroke, determine its type, and even estimate the dog’s age based on the characteristics of the MRI. Serial/repeat MRIs are sometimes utilized to monitor a lesion, especially if there is any concern about atypical features, history, or presentation of a case suggesting that a vascular event may not be likely.

Living with a stroke as a dog

Dogs may compensate for neurological losses better than humans in some cases. They can regain the ability to walk, see, or function near normal if the damage isn’t in a critical spot. Haemorrhagic strokes, while rarer, are more unpredictable – they carry a higher risk of acute complications or death, especially within the first day or two after the stroke, and, in some cases, may require emergency surgery. Suppose a dog survives the initial haemorrhage and the bleeding is controlled. In that case, they, too, can recover, but the early period is critical.

What affects the prognosis?

Additionally, suppose the MRI reveals an underlying condition (for example, an aggressive brain tumour or severe, uncontrolled high blood pressure). In that case, the overall prognosis is more guarded because the stroke is a symptom of a bigger ongoing problem. Dogs with significant comorbidities (other medical conditions) tend to have shorter survival times. They are at higher risk of having another stroke in the future. On the other hand, if no underlying disease is identified and the dog’s stroke is an isolated event, the long-term prognosis for recovery is much more favorable.

Conclusion

Access to MRI has changed how veterinary medicine thinks about vascular events in dogs, starting with how frequently they happen! MRI allows veterinarians to diagnose and evaluate rapid-onset neurological issues and can provide a high degree of information to veterinarians and owners regarding the underlying cause and associated damage. With knowledge comes power, and when it comes to strokes, an MRI can give us a lot of power!

Take a look at the case study below and see if you can answer this question:

Based on the findings in this MRI, what type of stroke/vascular event did this dog have?

Case in question

This 14-year-old small-breed dog was presented for acute onset of vestibular signs. He was localized to having a left paradoxical vestibular lesion with a high concern for a vascular event of the cerebellum.

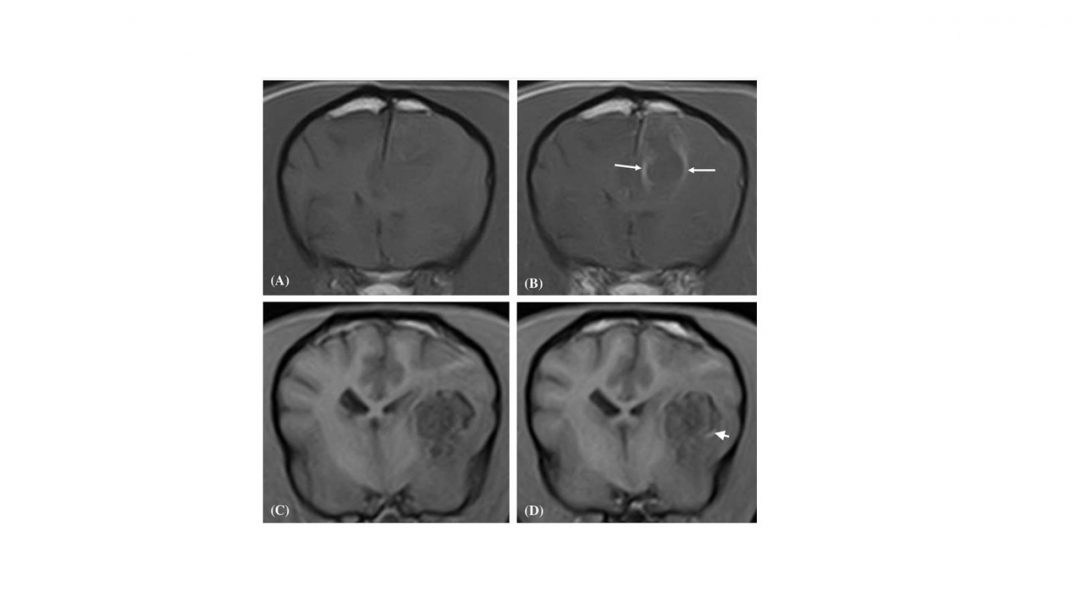

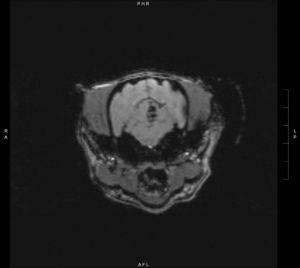

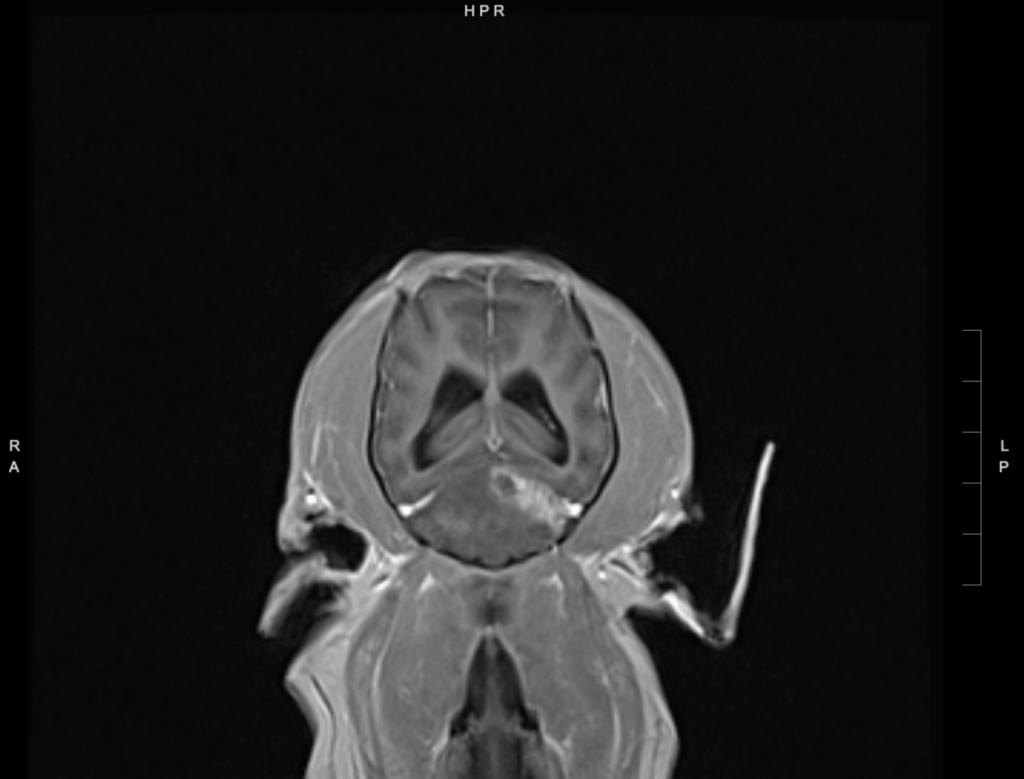

His MRI* revealed a lesion within the left-side of the cerebellar vermis that displays susceptibility artefact on the Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging (SWI) sequence (Fig. 1), consistent with susceptibility from iron in the blood. There is a large area of T2/FLAIR hyperintensity surrounding the T2 hypointense lesion involving much of the left and right cerebellar hemispheres, this can be seen in the cranial aspect of the cerebellum on the sagittal image (fig. 2) and likely represents perilesional edema. There is variable contrast enhancement surrounding the T2 hypointense lesion and extending into the left cerebellar hemisphere, seen on the dorsal plane image (Fig. 3).

Answer: Left sided cerebellar haemorrhagic stroke with perilesional oedema.

Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging (SWI), similar to a T2* sequence, highlights the magnetic susceptibility differences of various compounds including deoxygenated blood, blood products, iron and calcium. In other words, the MRI (a giant magnet) and its magnetic field is susceptible to anything with magnetic properties, such as the iron (a metal) that exists in our blood and this sequence leverages this interaction between the magnetic field and the metal in our blood to show us haemorrhagic lesions.

I’m sure all of our physics teachers would be beyond thrilled to know we are leveraging the power of physics in our daily lives!

*Images were collected from a 3.0T MRI.

For more information on The Brain Dogtor click here or follow on social media @thebraindogtor

For more information on MIRA, Hallmarq’s 1.5T MRI, click here