While ultrasound remains a valuable tool in equine lameness evaluations, for certain conditions like proximal suspensory ligament (PSL) injuries, it may not be enough. MRI provides unmatched detail and depth, making it an essential part of the diagnostic process when other tools fall short. Guest Author Ellen Law, ECVDI Resident from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences considers the pros and cons of ultrasound vs MRI for proximal suspensory ligament injuries. This in depth feature looks at how combining accurate imaging with clinical expertise, enables veterinarians to give owners the insights they need, and horses the best possible chance at a full recovery.

MRI: for when ultrasound fails to deliver

Lameness in horses is one of the most common – and often most frustrating – problems facing owners, riders, and veterinarians alike. While many injuries are straightforward to diagnose, issues involving the proximal suspensory ligament (PSL) are frequently more elusive. These deep soft tissue injuries can cause significant discomfort and performance limitations but may not always be visible with conventional imaging.

Ultrasound is often the first choice for imaging soft tissues like ligaments and tendons. It’s reliable, widely available, and can often confirm a diagnosis quickly. However, in some cases – especially involving subtle, chronic, or deep-seated injuries – MRI offers additional value by providing a more comprehensive picture.

This article explores why ultrasound can be limited for PSL diagnosis, and how MRI is transforming how we approach these complex injuries – both for veterinarians and the horse owners they serve.

What makes the PSL so challenging to assess?

The PSL is a key component of the suspensory apparatus that supports the fetlock joint and plays a vital role in equine locomotion. In the hindlimbs in particular, the proximal part of the ligament is located deep within the leg, adjacent to the cannon bone and partially beneath the lateral splint bone.

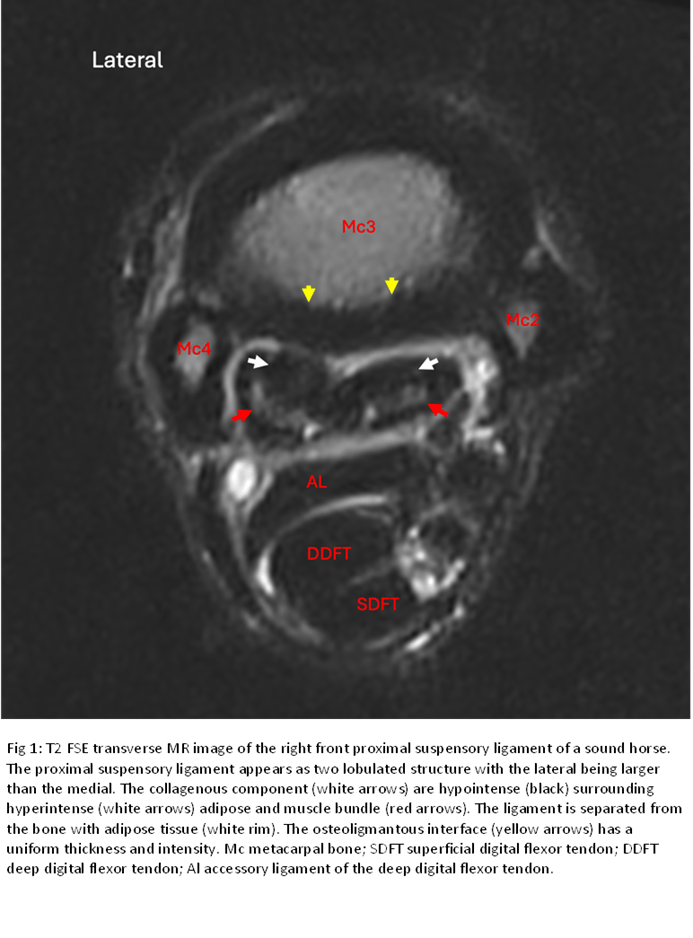

This deep anatomical location, combined with the ligament’s complex internal structure- which includes fat, muscular, and tendinous elements – makes accurate imaging and diagnosis a challenge. In addition, normal anatomical variation between horses can make it difficult to distinguish between subtle pathology and individual differences.

Although ultrasound is a valuable diagnostic tool, these factors can sometimes limit its ability to thoroughly assess the PSL, especially when more detailed imaging is required.

Limitations of ultrasound for PSL imaging

Ultrasound is a trusted, non-invasive tool that provides real-time insight into many superficial soft tissue structures. However, when it comes to the PSL- especially in the hindlimbs – ultrasound faces several key limitations:

- Restricted acoustic access: The PSL’s deep location and surrounding bony structures can prevent adequate visualisation, particularly in the transverse and axial planes (Denoix, 1994; Denoix & Jacot, 1996).

- High operator dependency: Subtle changes in technique, pressure, or angle can dramatically affect image appearance. Consistency across operators is difficult to achieve (Whitcomb, 2006).

- Subtle pathology may be missed: Early-stage PSL injuries, particularly those involving mild inflammation or small fibre disruptions, may not show up on ultrasound (Dyson et al., 2005).

- Bone-related changes: Often, there are concurrent lesions in the bone surface on the backside of the cannon bone, and ultrasound has limitations in detecting such changes.

For these reasons, even experienced veterinarians may be unsure of a diagnosis when relying solely on ultrasound – particularly in sport horses with mild or intermittent lameness.

MRI may offer a better view

MRI has become a game-changer for diagnosing musculoskeletal conditions in horses, particularly deep soft tissue injuries like those affecting the PSL. Here’s why:

- Superior soft tissue contrast: MRI can detect inflammation, fibre disruption, fluid accumulation, and even early degenerative changes within the ligament (Murray et al., 2008).

- Multi-planar imaging: MRI captures images in multiple planes (sagittal, transverse, and dorsal), offering a complete 3D view of the PSL and surrounding structures.

- Identification of concurrent pathology: MRI can reveal additional problems, such as bone oedema, joint inflammation, or injury to adjacent tendons, often missed on ultrasound (Schramme et al., 2010).

- Safe and now more accessible: With more standing MRI systems available, horses can undergo scanning without general anaesthesia, significantly reducing risk and cost (Kinns et al., 2006).

Importantly, MRI is not just about finding pathology, it’s about understanding the nature and extent of an injury. This helps us to tailor treatment more precisely, whether through rest, shoeing, controlled exercise, regenerative medicine or even surgical options like fasciotomy.

iNAV: the new sequences for advanced motion correction

For imaging of the proximal suspensory ligament (PSL), the new Hallmarq iNAV sequences have truly revolutionised equine MRI. With enhanced contrast, improved anatomical detail, and significantly reduced motion artefacts during scanning of the proximal limb, iNAV makes it easier to detect subtle ligament and bone changes that might otherwise go unnoticed.

When should MRI be considered?

MRI is particularly valuable when:

- Clinical signs point to PSL injury, but ultrasound is inconclusive.

- A horse is not responding to treatment as expected.

- Lameness is chronic or recurring, especially in performance horses.

- The clinician suspects multiple or complex lesions that need a full anatomical overview.

While MRI may not be necessary for every lameness case, it can prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary delays when standard imaging doesn’t provide answers.

For horse owners: what this means for you

If your horse has persistent lameness and no clear diagnosis has been made, it’s reasonable to ask your vet whether MRI might help. It’s especially useful in high-level sport horses, horses not responding to treatment, or cases where a PSL injury is suspected but can’t be confirmed on ultrasound.

Although MRI is more expensive than ultrasound, it often saves time and money in the long run by giving clear answers and guiding effective treatment.

Conclusion

When considering ultrasound vs MRI for proximal suspensory ligament (PSL) injuries, ultrasound remains a valuable tool in equine lameness evaluations. However, for certain conditions like proximal suspensory desmitis, it may not be enough. MRI provides unmatched detail and depth, making it an essential part of the diagnostic process when other tools fall short.

By combining accurate imaging with clinical expertise, veterinarians can give owners the insights they need – and horses the best possible chance at a full recovery.

Case Example

Diagnosing proximal suspensory ligament injury with MRI

An 8-year-old Swedish Warmblood mare presented with intermittent lameness in her right front (RF) limb for the past six weeks, which blocked to analgesia of the deep branch of the lateral palmar nerve.

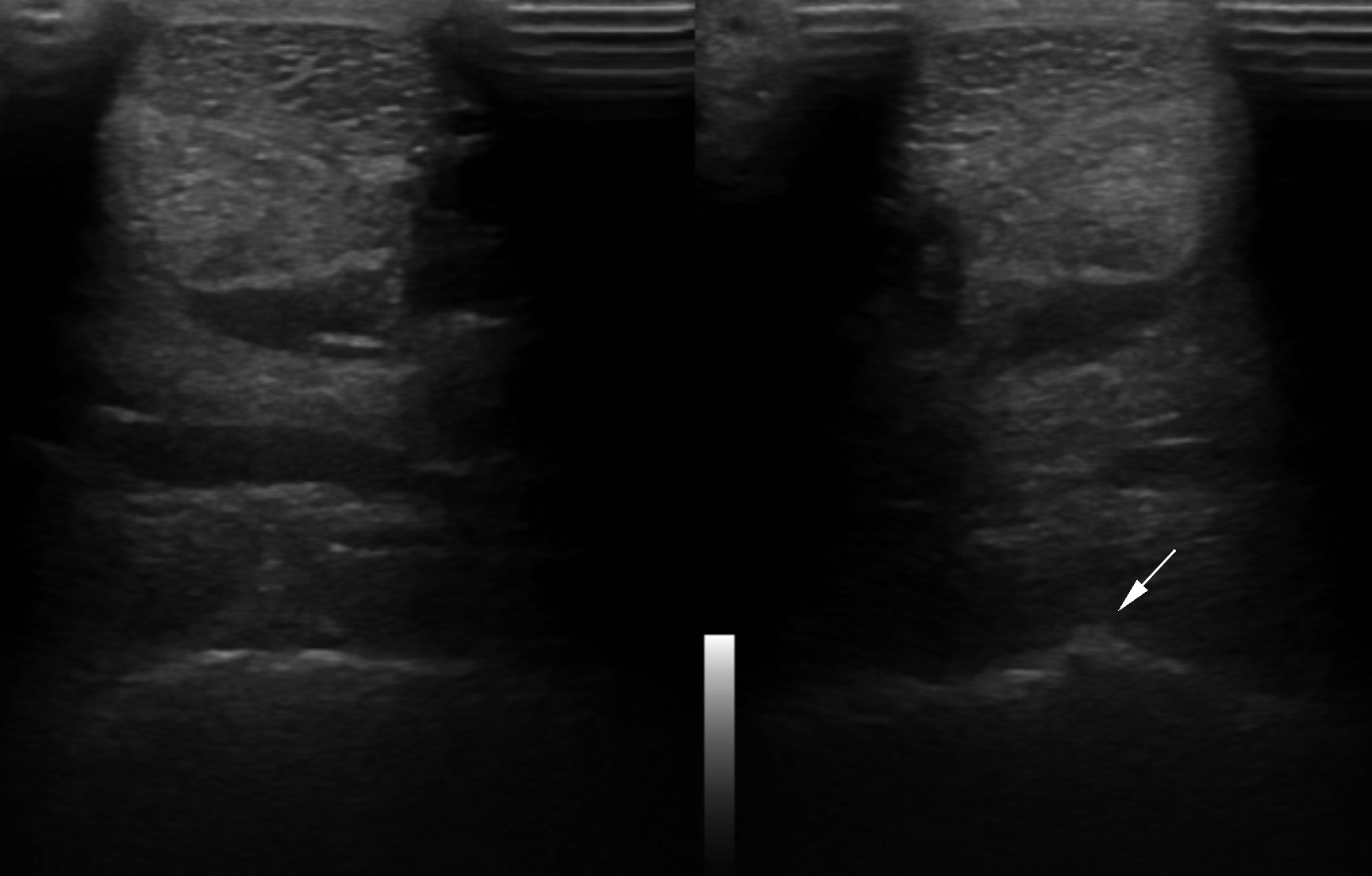

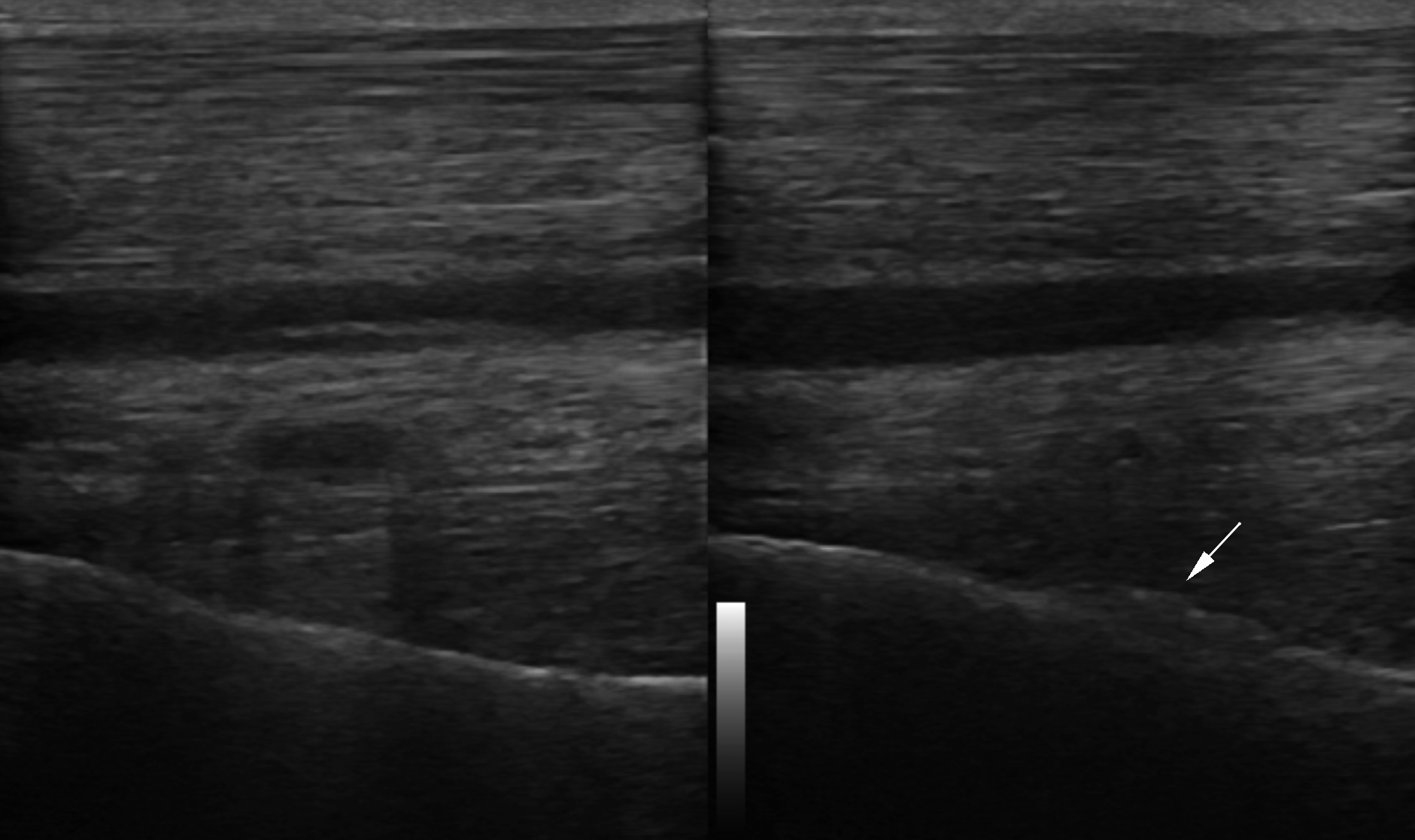

Ultrasonography

The initial ultrasound, performed by an experienced sonographer, showed rough bone surface in the proximal attachment of the suspensory ligament (Fig.1 and Fig.2) but no abnormalities in the ligament itself. The findings were attributed to possible old changes. Radiographs showed no significant issues, and the mare was placed on rest and anti-inflammatory medication.

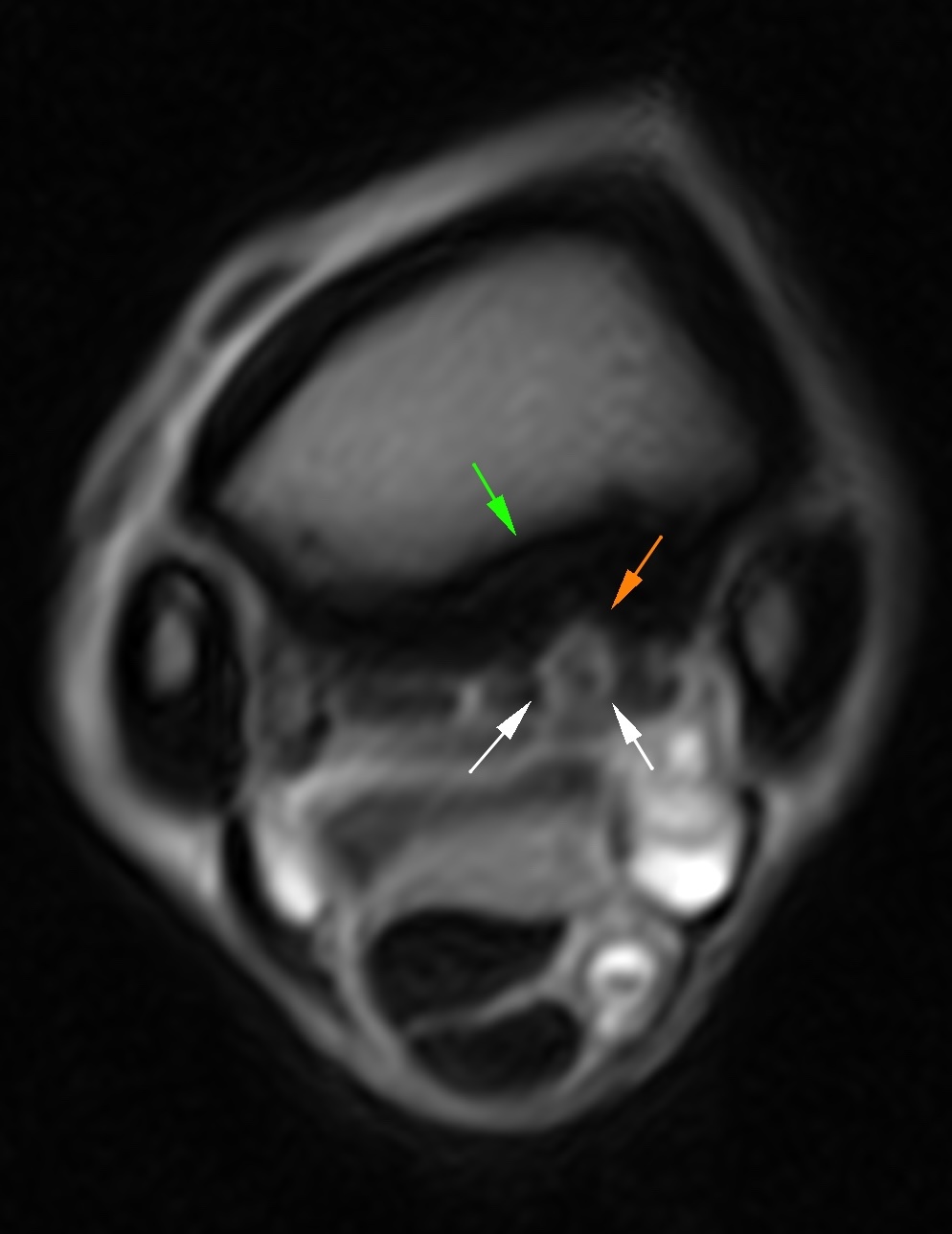

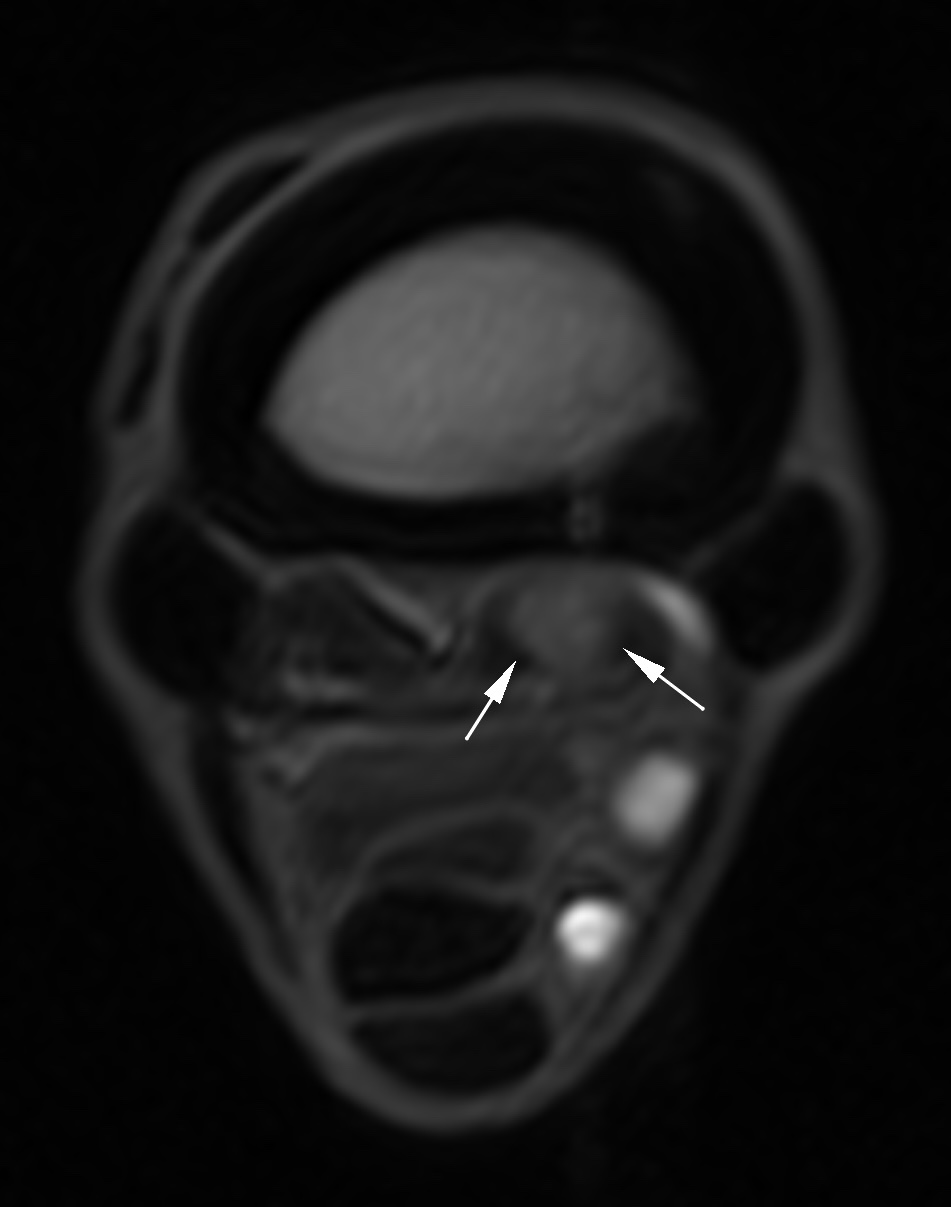

MRI

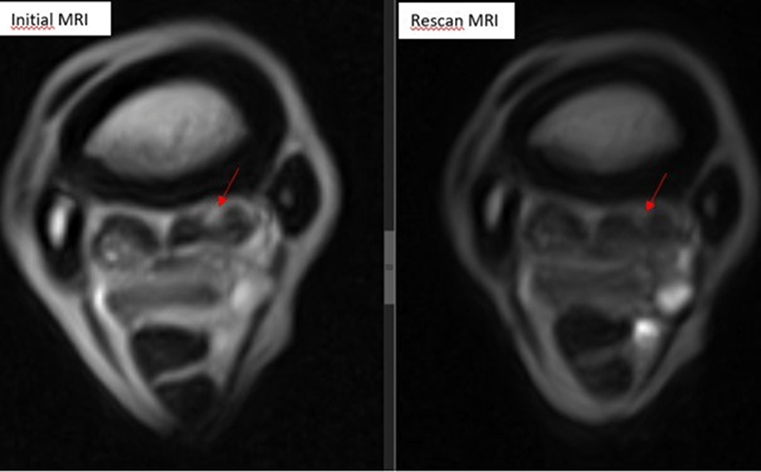

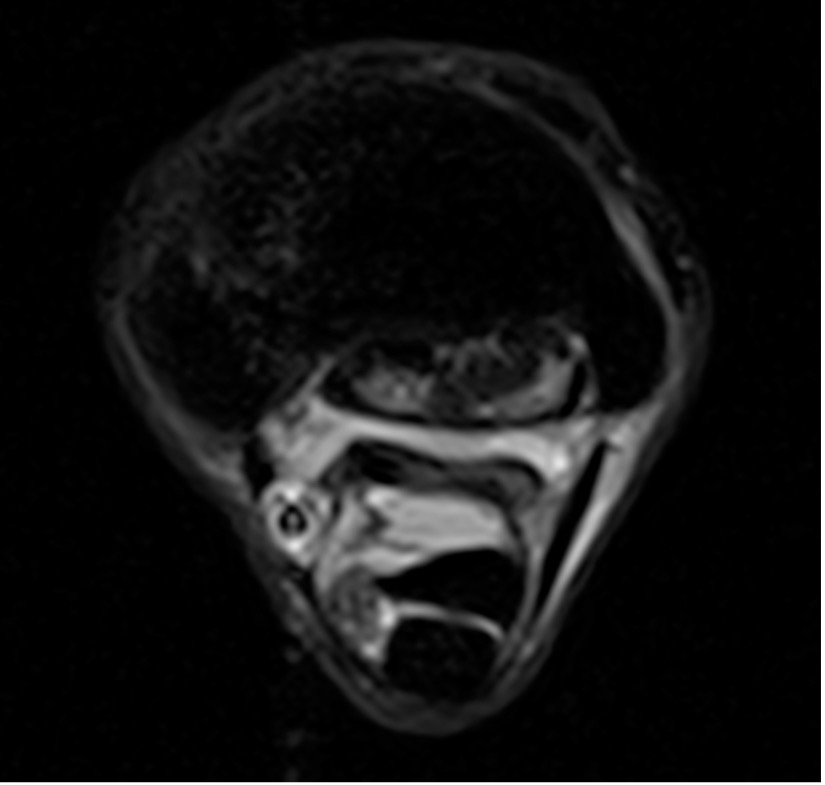

Despite following the treatment plan, the lameness persisted, prompting a referral for MRI. The standing MRI revealed a moderate, focal injury to the medial lobe of the right front suspensory ligament at its proximal attachment, with involvement of the third metacarpal bone. The injury spanned 3.5cm, with damage extending into the bone, showing STIR hyperintensity (oedema, haemorrhage, inflammation, necrosis, neovascularisation, fibrosis), and extensive surrounding sclerosis. Additionally, there was a mild injury to the MC2-MC3 interosseous ligament.

Conclusion

When considering ultrasound vs MRI for proximal limb (PSL) injuries, this case highlights the limitations of ultrasound in detecting subtle proximal suspensory ligament injuries. The MRI provided the detailed imaging needed to accurately diagnose the ligament desmitis and bone injury, leading to a more targeted treatment plan.

Further reading and references

- Denoix, J.M. (1994). Functional anatomy of tendons and ligaments in the distal limbs. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice, 10(2), 273–322.

- Denoix, J.M., & Jacot, S. (1996). Ultrasonographic examination of the proximal suspensory ligament in the horse. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the AAEP, 42, 167–169.

- Dyson, S., Murray, R., Schramme, M., & Branch, M. (2005). Ultrasonographic assessment of the proximal suspensory ligament in hindlimbs of lame and control horses. Equine Veterinary Journal, 37(4), 376–382.

- Kinns, J., Mai, W., & Puchalski, S. (2006). Magnetic resonance imaging of the equine limb: Technique and clinical applications. Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice, 5(3), 294–307.

- Murray, R.C., Dyson, S.J., Tranquille, C.A., & Adams, V. (2008). Magnetic resonance imaging of the proximal suspensory ligament in hindlimbs: A comparison with ultrasonography and histopathology. Equine Veterinary Journal, 40(1), 37–43.

- Schramme, M., Dyson, S., Murray, R., & Smith, R.K. (2010). Deep tissue injury and MRI findings in equine limbs. Equine Veterinary Education, 22(8), 376–389.

- Whitcomb, M.B. (2006). Ultrasonographic evaluation of the suspensory ligament. Clinical Techniques in Equine Practice, 5(3), 266–276.