Tremors in dogs and cats are common presenting complaints. When a pet presents with tremors, a frequently encountered question for the clinician is “To scan, or not to scan?” Guest author Theofanis Liatis, DVM MVetMed PhD DipECVN FHEA MRCVS EBVS® and RCVS European Diplomate in Veterinary Neurology, obtained his PhD diploma in ‘Tremors in dogs and cats’ at the University of Ghent in 2024. As a specialist on the subject, Fanis discusses the dilemma of whether to scan or not and offers a framework of clinical parameters to help with decision making.

Clinical parameters to help with decision making

3+1 clinical parameters are of crucial importance on decision making for advanced imaging in pets with tremors:

(1) Signalment and presentation

Species, breed, sex, age at onset and presentation of tremors are crucial information to assist the clinician to narrow down the differential diagnoses. For instance, hyperacute nonprogressive generalised tremors in dogs have been associated with intoxication. Acute progressive generalised tremors, with accompanying often lateralizing vestibulocerebellar signs, have been associated with idiopathic generalised tremor syndrome (IGTS). Additionally, generalised tremors soon after birth (2-4 weeks old) in both dogs and cats may be associated with a congenital hypomyelinating or dysmyelinating disease (leukodystrophy).

(2) Type of involuntary movement

It is important for a clinician to describe the involuntary movements that the pet is having. Is the involuntary movement:

- A tremor (rhythmic sinusoidal oscillation)

- Myoclonus (shock-like jerk usually causing movement of a part of the body away from it)

- Fasciculation (vermicular movements under the skin due to peripheral nerve hyperexcitability)

- Dystonia/dyskinesia (sustained increased muscle tone that may lead to abnormal posture or gait)

- Epileptic seizure

A useful clinical feature is the distractibility. No animal can be distracted out of an epileptic seizure. When an animal can be distracted out from an episode, then this episode probably represents likely a functional movement or behavioural disorder. If the limb tremors are chronic and postural, then they are most likely benign (e.g. benign idiopathic rapid postural tremor [BIRPT] or orthostatic tremor). If the tremors are intentional – and there is no exposure to toxins – a cerebellar disease should be suspected and MRI should be pursued. Periodicity of the tremor also may play a role in decision making. For instance, in a case with episodic tremor and no other neurological deficits (e.g. idiopathic episodic head tremor) it is less likely to find a structural lesion in the MRI.

(3) Somatotopy

Somatotopy refers to the precise mapping of body parts to specific areas of the brain, where stimulation of cortical points corresponds to the activation of individual muscles. Whether the involuntary movement occurs only on the head, in the limbs or the whole body may reflect to its potential localisation. For instance, a pelvic limb myoclonus is likely to be originated in the spinal cord, whereas a whole-body myoclonus most likely in the brain.

(4) Electromyography

(Conscious +/- under sedation or general anaesthesia) usually is helpful to distinguish the type of involuntary movement (e.g. tremor vs peripheral nerve hyperexcitability) and assist the clinician to narrow down the differential diagnoses.

History, signalment and baseline blood tests are crucial

A history of scavenging and a hyperacute nonprogressive onset of generalised tremors that does usually resolve within 48 hours without corticosteroids raises a suspicion of acute intoxication. Moreover, any metabolic cause of tremors should be ruled out prior to any MRI scan. Therefore, a basic diagnostic panel including CBC (with blood smear), serum biochemistry (with glucose and electrolytes including ionised calcium and ideally magnesium), ammonia +/- bile acid stimulation test should be considered as the baseline for tremor cases.

When is an MRI scan in dogs and cats with tremors NOT needed?

In generalised tremors in dogs, the most common diagnosis is intoxication. In intoxication and metabolic diseases, an MRI of the brain is not necessary. The second most common diagnosis in dogs with generalised tremors is IGTS. These dogs present with acute progressive with often lateralising vestibulocerebellar signs, and the MRI of the head is usually normal. CSF analysis may be consistent with lymphocytic pleocytosis, albuminocytological dissociation or normal.

When is an MRI scan in dogs and cats with tremors necessary?

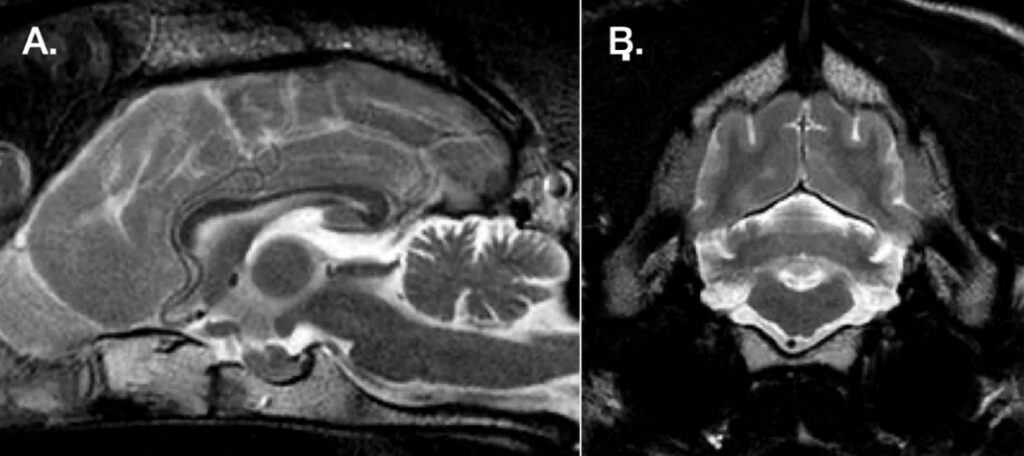

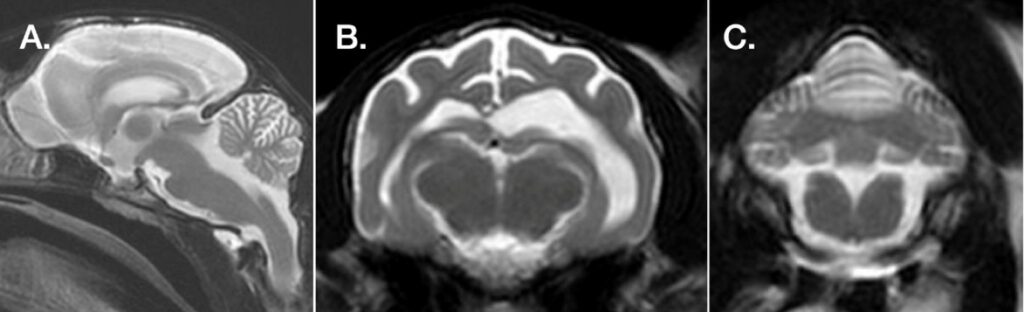

Intention head tremor

When intention head tremors are accompanied by other signs of cerebellar disease (e.g. hypermetria, head tilt, wide based stance etc.), an MRI may be useful to investigate structural disease of the cerebellum. Intention head tremors were mostly associated with degenerative encephalopathies in cats, and specifically cerebellar cortical degeneration (abiotrophy). MRI in these cases is usually consistent with diffuse cerebellar atrophy (Figure 1).

Episodic head tremor

Idiopathic episodic head tremor is a benign tremor of young purebreds (e.g. Bulldogs). This tremor is considered a functional tremor and MRI is not necessary as the brain is normal. However, in older dogs with accompanying neurological deficits, a structural lesion affecting the thalamus or mesencephalic aqueduct may be present. In such cases, MRI is warranted.

Limb tremor

Limb tremors, and especially postural (ie. Orthostatic tremor, BIRPT), in absence of other neurological signs are usually functional tremors. This means, that MRI will not show any structural lesion in the central nervous system. However, in rare cases with accompanying neurologic deficits (e.g. orthostatic tremor plus), MRI of the vertebral column and the brain or/and electromyography may be needed to investigate an underlying condition. Limb tremors at rest, along with decreased spinal reflexes and muscle tone, are also seen in patients with neuromuscular disease, in which an MRI is not part of the investigations.

Generalised tremor

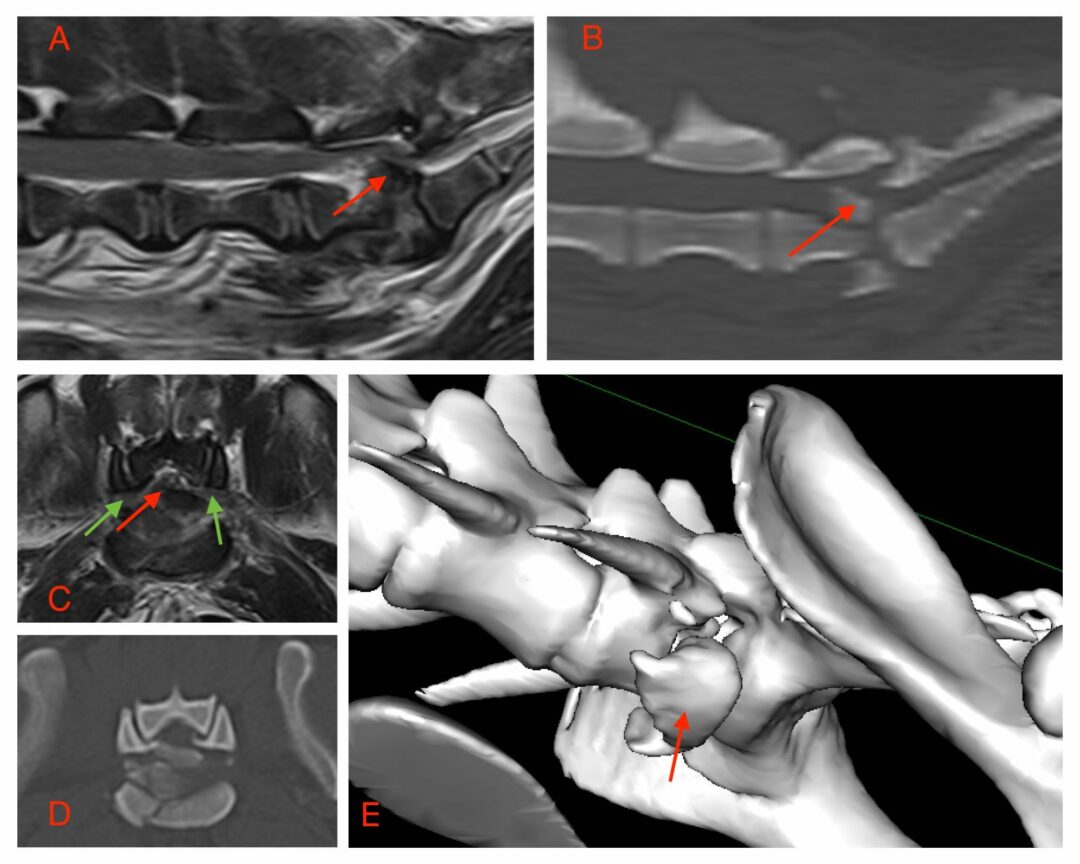

As stated above, the two most common causes of generalised tremors in dogs either do not require an MRI (e.g. intoxication) or they have a normal brain (e.g. IGTS). However, in rare cases with specific signalment, history and presentation, an MRI should be considered after having ruled out a toxic and metabolic cause. Inherited degenerative encephalomyelopathies (Figures 1, 2 & 3) involving the myelin of the white matter diffusely (generalised tremor) or the cerebellum (intention head tremor) should be considered to cause tremors, in which MRI may be necessary.

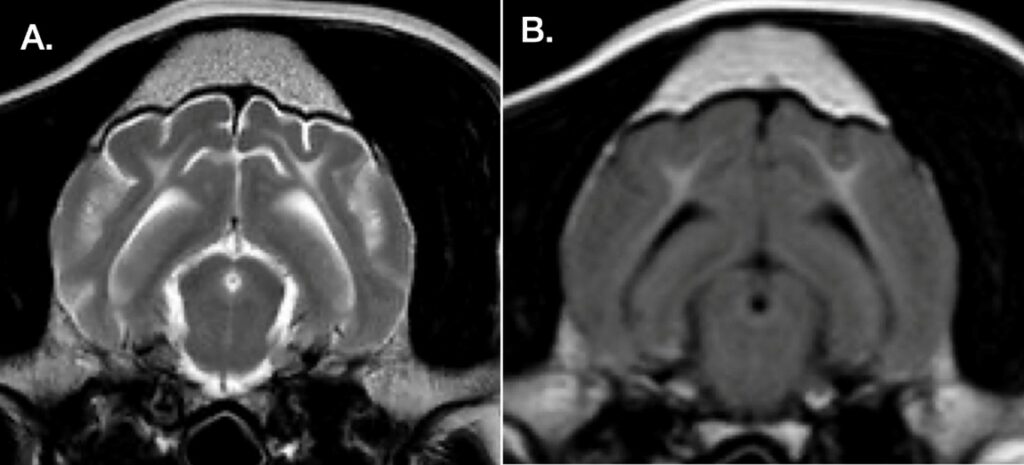

Leukodystrophies: a cause of tremors in puppies and kittens

A hypomyelinating leukodystrophy should be considered in young puppies or kittens with an onset of generalised tremors around 2-4 weeks of age that may improve over time. Spongiform leukodystrophies (e.g. Border Terriers, German Shepherds) or other dysmyelinating leukodystrophies (e.g. fibrinoid leukodystrophy or Alexander disease) can manifest with tremors. Hypomyelination in MRI may be subtle and consistent with a delay in the development of T2W hypointensity and, often, T1W hyperintensity in the white matter of the brain compared with healthy controls of the same age.

In general, demyelination is not usually leading to tremors; however, when demyelination is diffuse tremors may occur. The most characteristic of degenerative diseases that may lead to tremors as a result of diffuse demyelination is globoid cell leukodystrophy (GCL), in which T2W hyperintensity of the white matter may be seen (Figure 2). A few dogs with meningoencephalitis of unknown origin (MUO) or cats with CNS lymphoma may manifest generalised tremors; these pets require an MRI scan with subsequent CSF analysis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although most dogs and cats presenting with tremors do not require an MRI scan, in certain circumstances a thorough attention to history, signalment, tremor phenotype and other clinical features of each case may lead to the necessary decision to pursue an MRI scan to identify the underlying disease, assist on therapeutic planning and establish prognosis.

Suggested bibliography

- Barkovich AJ, Deon S. Hypomyelinating disorders: An MRI approach. Neurobiol Dis 2016; 87: 50-8.

- Liatis T, Bhatti SFM, De Decker S. Generalized Tremors in Dogs: 198 Cases (2003-2023). J Vet Intern Med 2025; 39: e70062.

- Liatis T, Bhatti SFM, De Decker S. Tremors in cats: 105 cases (2004-2023). Vet J 2025 Feb; 309: 106292.

- Quitt PR, Brühschwein A, Matiasek K, Wielaender F, Karkamo V, Hytönen MK, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Dengler B, Leeb T, Lohi H, Fischer A. A hypomyelinating leukodystrophy in German Shepherd dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2021; 35: 1455-1465.

- Miguel-Garcés M, Gonçalves R, Quintana R, Álvarez P, Beckmann KM, Alcoverro E, Moioli M, Ives EJ, Madden M, Gomes SA, Galban E, Bentley T, Santifort KM, Vanhaesebrouck A, Briola C, Montoliu P, Ibaseta U, Carrera I. Magnetic resonance imaging pattern recognition of metabolic and neurodegenerative encephalopathies in dogs and cats. Front Vet Sci 2024; 11: 1390971.

Photo credit © Drew Bird Photography, Inc.