This month, guest blogger Dr. Mahmoud Mageed from Equipixel Veterinary Teleradiology writes on the subject of imaging the proximal suspensory ligament. His article outlines the need for an accurate understanding of this complex structure when diagnosing and treating injuries, and the available imaging modalities that may help.

Diagnosing desmopathy

Horses have undergone significant evolutionary changes, transitioning from walking on their soles to walking on their toes. This transformation has led to substantial alterations in their limb structure, particularly in the medial (third) interosseous muscle, commonly known as the suspensory ligament. This ligament, crucial for limb biomechanics, comprises a mix of tendinous and skeletal muscle fibers, with the proportion of muscle fibers varying from 2% to 15%, and occasionally up to 40%. An accurate understanding of its structure is essential for diagnosing and treating injuries, especially in the hind limbs. Although the term “tendinopathy” is technically correct, “desmopathy” is commonly used in literature to describe injuries to this “ligament”.

Anatomy and injury prevalence

The proximal suspensory ligament originates at the proximal metacarpus/metatarsus and extends between the splint bones to the distal cannon bone, where it splits and attaches to the proximal sesamoid bones. Injuries to the suspensory ligament are common, with a prevalence of up to 31% in non-race sport horses, especially dressage horses and show jumpers.

Radiography

Radiography is often the first imaging modality used to assess suspensory ligament injuries. It reveals changes at the osteoligamentous interface, such as increased bone density (sclerosis) and periosteal or endosteal proliferation. However, radiographic changes are usually chronic since around 30% of bone density must change to be visible radiographically, limiting its usefulness for acute injuries. Radiography also provides limited information on soft tissues.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound offers valuable insights into the shape, size, and fiber pattern of the suspensory ligament, as well as the osteoligamentous interface. The most common abnormality detected is ligament enlargement, visible as a reduced distance between the ligament’s dorsal border and the cannon bone. Severe cases may show compression of vascular vessels and intraligamentous adipose/muscular tissues. Evaluating the ligament in a non-weight-bearing limb helps differentiate its collagenous fibers from muscle fibers. However, ultrasound cannot reliably determine the timeline of an injury (acute vs. chronic; active vs. inactive), which is important for treatment and rehabilitation planning.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

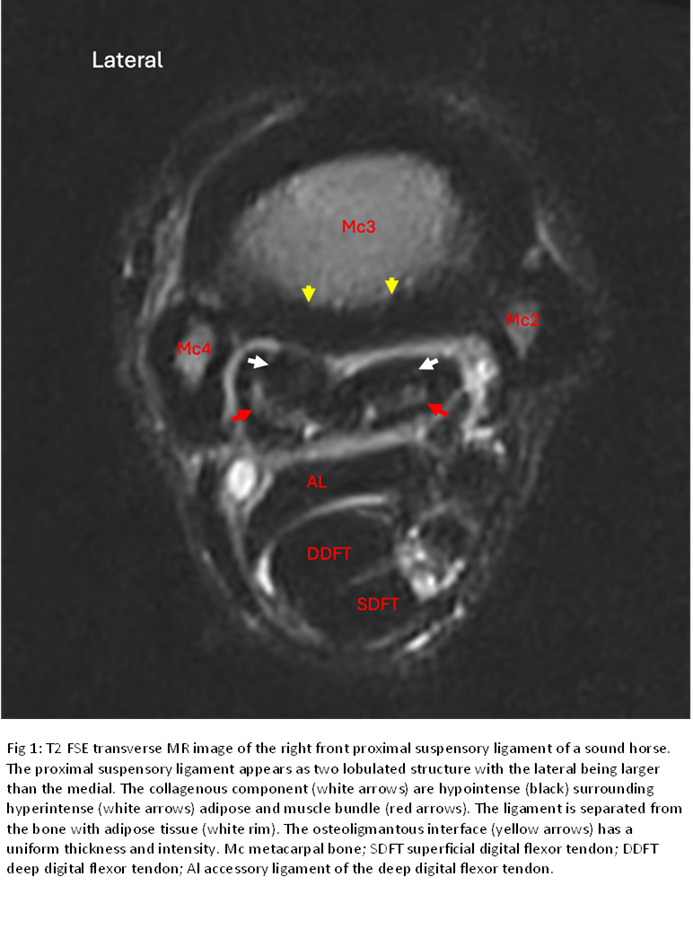

MRI provides detailed information about both bone and soft tissues of the proximal suspensory ligament. Normal MRI appearance (Fig. 1) shows hypointense (black) collagenous fibers surrounding a hyperintense (white) center representing adipose and muscular fibers. The muscle areas are crescent-shaped and symmetrically distributed compared to the contralateral limb. In the forelimb, the proximal suspensory ligament appears as two distinct lobes, with the medial lobe being smaller and flat/oval, while the lateral lobe is rounded. In the hind limb, the lateral lobe is twice as large as the medial.

Standing MRI is now available for horses, allowing for re-evaluation of the proximal suspensory ligament post-injury to design optimal therapeutic and rehabilitation plans without the risks associated with general anesthesia.

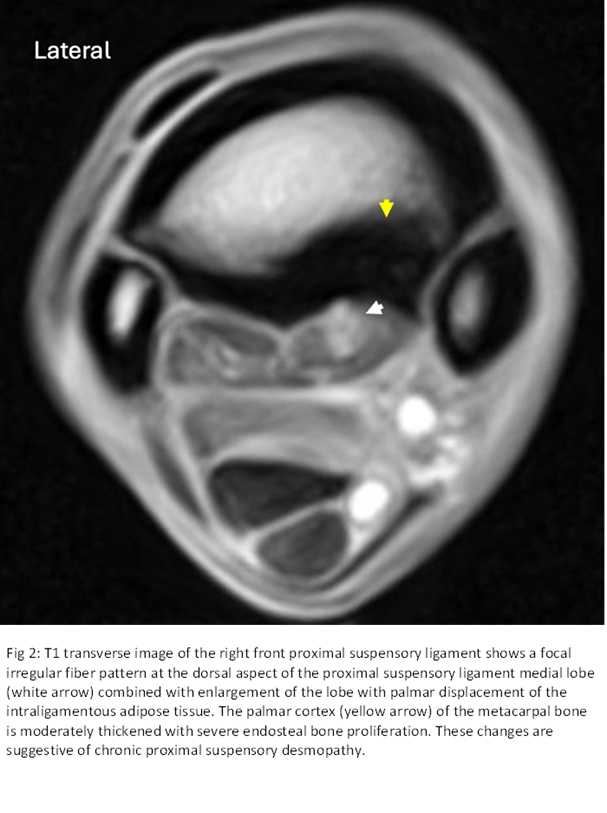

In cases of proximal suspensory desmopathy (Fig. 2), the ligament shows an inhomogeneous fiber pattern in the collagenous component, with poorly distinct adipose-muscle tissues. Fluid accumulation in the fat-muscle bundle area appears more hypointense (black). Such subtle changes are difficult to detect with other imaging modalities. Enlargement of the ligament, often seen in heavily trained sound horses, is considered an adaptation process, necessitating adjustments in training programs to prevent serious injuries. Bone edema, indicating increased fluid signal (STIR hyperintensity) in the bone, can be diagnosed exclusively using MRI and suggests bleeding, edema, fibrosis, or necrosis due to degeneration or trauma.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT has been proposed as an alternative to MRI, due to its high resolution and quick acquisition time. While CT excels at providing detailed anatomical images of osseous structures, it offers limited information for soft tissues. Differentiating between lesions and normal intraligamentous tissues can be challenging with CT. To enhance CT’s effectiveness in diagnosing suspensory ligament injuries, contrast enhancement CT (angiography) has been suggested. This minimally invasive technique could improve the visualization of soft tissue lesions mainly acute injuries, but its application is still not well-documented. Other lesions such as bone edema cannot be detected in the CT, even if a contrast agent is used. Although dual CT is used to detect bone edema in humans, its use in equine is currently limited to cadaver studies.

Summary

The suspensory ligament’s anatomy is crucial for diagnosing injuries, which are common in sport horses. Various imaging methods like radiography, ultrasound, MRI, and CT help evaluate these injuries, with MRI offering detailed bone and soft tissue evaluation.

INTERESTED IN VISIONARY VETERINARY IMAGING?