Introduction to Standing Equine MRI

With over two decades of experience in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and a commitment to advancing equine veterinary care, Hallmarq pioneered the world’s first and only Standing Equine MRI (sMRI) machine. Now considered the gold standard for imaging the foot of the standing horse, this unique imaging modality brings the same diagnostic capability to equine clinical practice as human MRI. With optimal horse health at the forefront of every design decision, standing MRI provides excellent soft tissue and bone imaging in a safe, effective, and affordable procedure without general anesthesia.

In this comprehensive Guide to Standing Equine MRI, we answer your questions on how this technology works and the benefits and capabilities of Standing Equine MRI in diagnosing and treating lameness in horses.

How Standing Equine MRI Works

Standing Equine MRI is a low-field MRI procedure performed while the horse remains standing. This specially designed scanner is safe for the horse and handler and is carried out with gentle sedation for the patient. By visualizing slices through tissue, standing MRI can quickly and precisely localize damage to bone and soft tissues without general anesthesia.

So, how does it work? MRI technology relies on strong magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses. These magnetic fields align the protons inside the body’s hydrogen atoms. When radiofrequency pulses are applied, they disrupt this alignment. As the atoms return to their normal state, they emit captured signals to create cross-sectional images that show the differences between various tissue types. Although classed as a low field, the magnet used in a standing MRI machine is incredibly powerful at 0.27 Tesla. However, as MRI does not use ionizing radiation, the magnetic field or the radiofrequency waves are not harmful to your horse or people, making it safer for repeated use.

Preparation for Standing MRI

Ensuring the patient is well-prepared and relaxed before a standing MRI will pay dividends. The time taken to prepare your horse for its standing equine MRI scan is invaluable.

The connection between the horse and the image is invaluable, and looking at the lameness pattern on the day of the scan benefits the outcome. Your veterinarian will discuss the case with the referral practice ahead of the day and provide as much helpful information as possible. It is also essential for the veterinarian to see and evaluate the feet. Information on the shoe, trimming, balance, and any distortion to the coronary band will help them interpret everything they see on the MRI images.

- Any metallic objects will distort the image, and steel horseshoes could become stuck to the magnet, putting the horse and handler in danger.

- Ahead of the scan, the horse’s shoes must be removed. In most cases, just two shoes must be removed: the leg to be scanned and the adjacent leg.

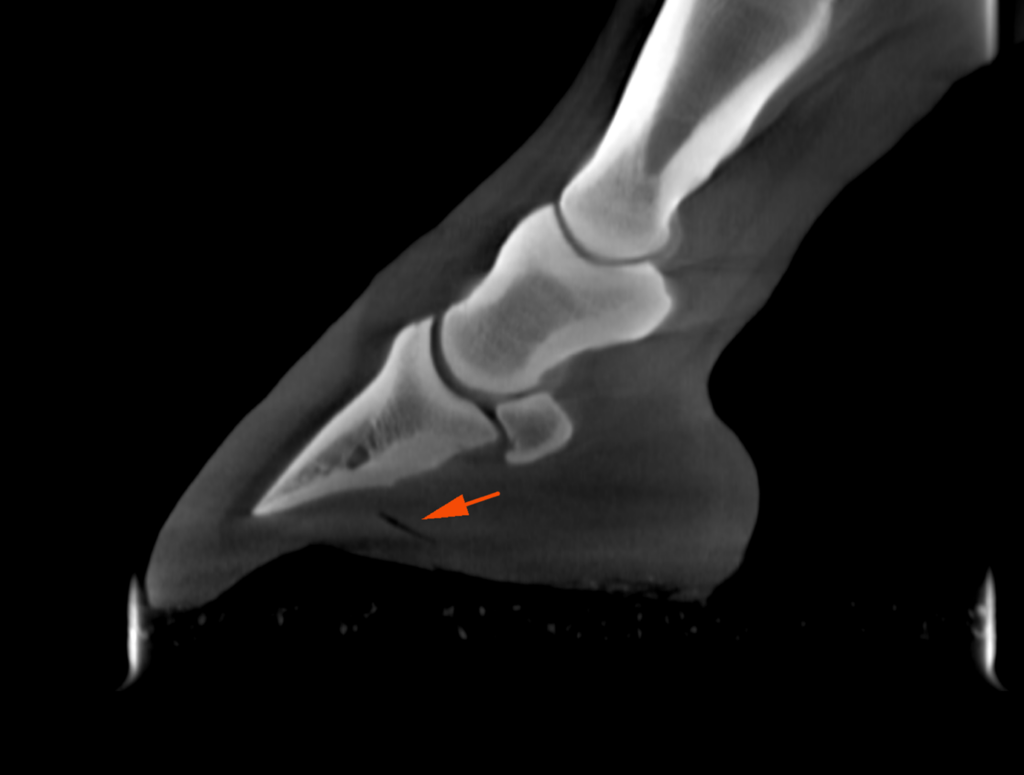

- Most practices take one or two X-rays before performing the MRI to help check for clenched (metal) fragments, which can cause artifacts (distortion) in the images. See Fig. 1 below

- The horse’s legs should be clean and dry and free from any blue or purple antiseptic sprays that will affect image quality if not removed

- Once at the veterinary practice, the horse should be given time to stand in the stall, urinate, and settle before going into the scan room

- Once the horse is in the scan room, the end goal is a comprehensive set of high-quality sequences taken from the region of interest in a reasonable time.

- A scan of a single foot can take 45-60 minutes; for a foot, a pastern fetlock can take around three hours.

Procedure Overview

When diagnosing equine lameness, acquiring the best possible MRI images starts long before the patient enters the MRI room.

- MRI poses no risk to the patient as a highly safe diagnostic imaging modality

- Your horse will not require general anesthesia, but a small amount of gentle sedation will be administered to help it remain calm throughout the procedure

- An experienced veterinarian will choose the appropriate type of sedation based on the individual patient’s health condition and the scan duration

- They will closely monitor the horse’s vital signs throughout the procedure to ensure safety

- Once prepared for scanning, the sedated horse is walked into the MRI scanner, and the lame leg is placed between the magnet’s poles.

- Careful positioning of the limb to be scanned is vital if clinically diagnostic images are to be taken

- To enable the capture of quality images, a radiofrequency coil is fitted around the injury site

- The operator makes any adjustments to ensure that both the patient and system magnet are in the right place

However, even the most docile horses will sway or move slightly when standing, and this movement changes the shape of the joint as the horse shifts its weight distribution. Hallmarq’s Standing Equine MRI incorporates our award-winning motion correction software. This technology – unique within the equine industry -is designed to compensate for any slight movement of the horse’s limb throughout the imaging process. It helps enable faster scan times to provide detailed clinical images of each horse the veterinarian sees.

MRI scanning can be a slow process to obtain clinically diagnostic images. Typically taking 1-3 hours, most horses can be seen on a day-patient basis. If scans of multiple areas (e.g., feet and fetlocks) are required, your veterinarian may recommend that the horse stays overnight and be imaged over two days to avoid large amounts of sedation on one day.

Applications and Uses of Standing MRI

Diagnostic in over 90% of cases, Standing Equine MRI is one of veterinary medicine’s most valuable non-invasive imaging technologies. Often considered the gold standard for assessing soft tissue injuries, it is also extremely useful for identifying bone pathology. MRI provides valuable information about a lesion’s pathological status and severity, even when conventional radiographs appear normal.

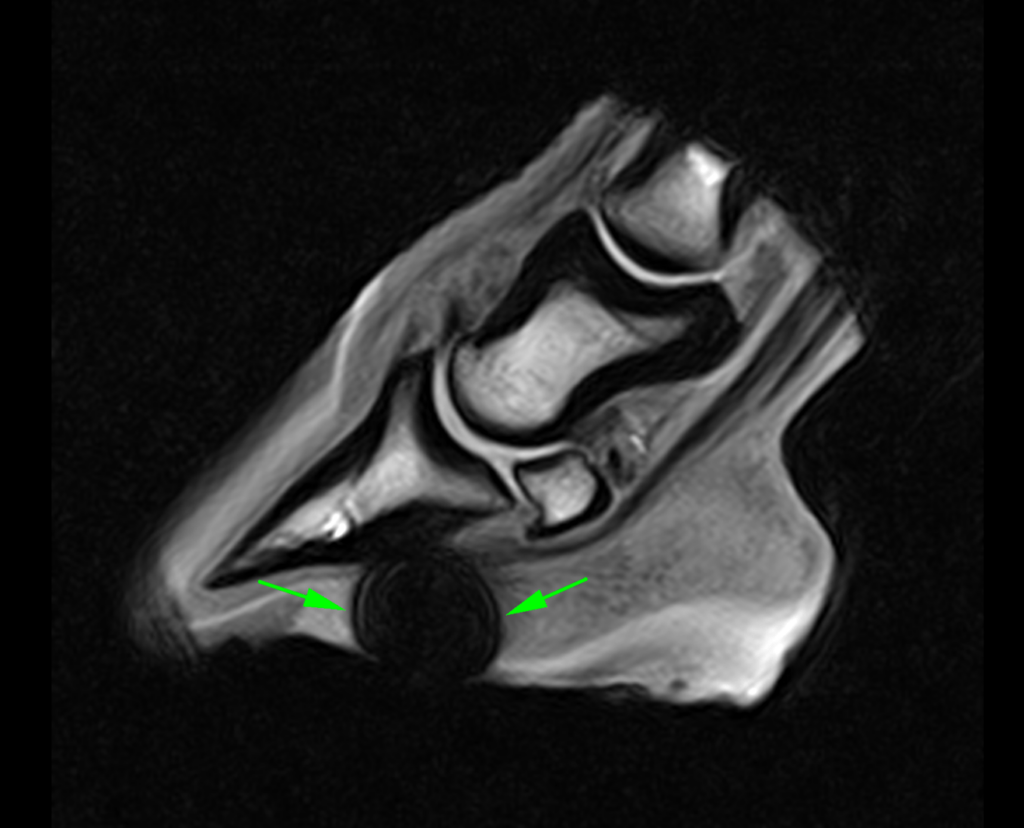

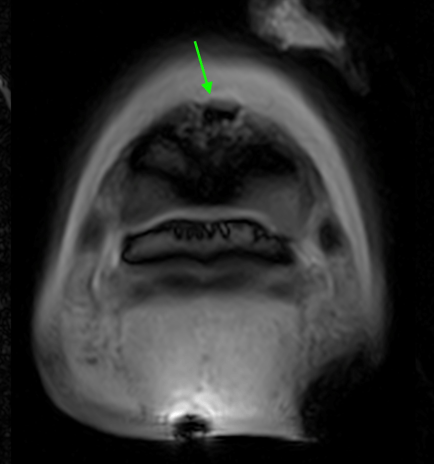

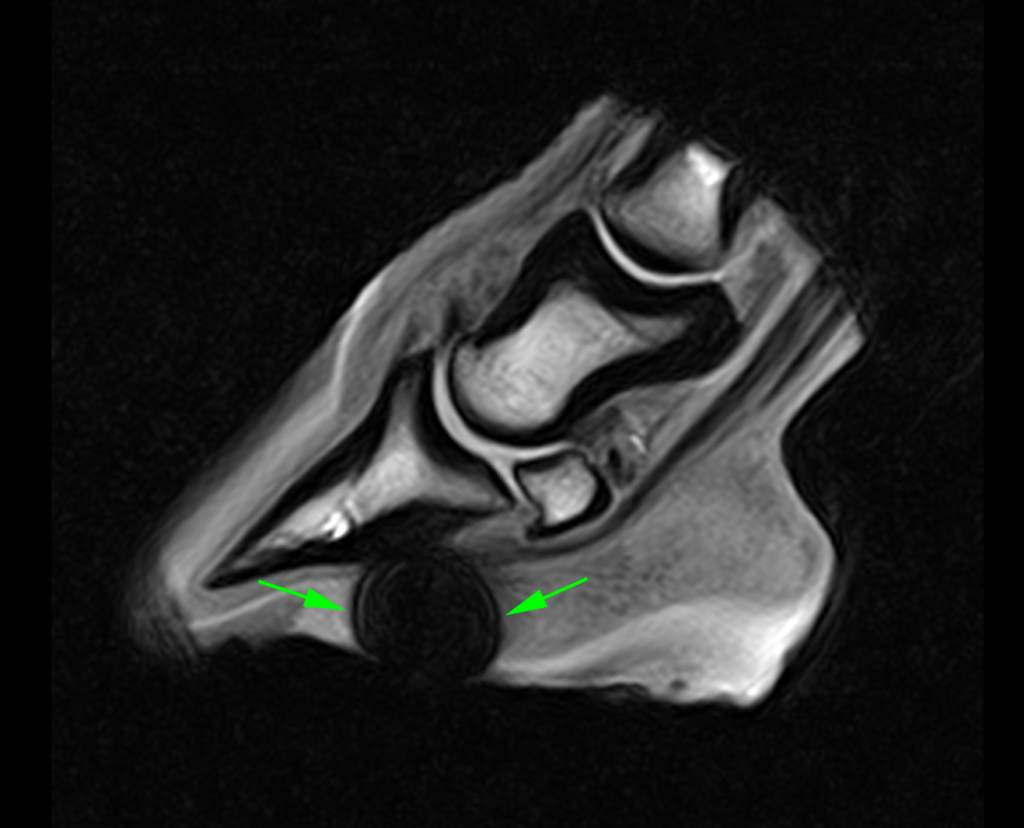

The use of standing MRI has revolutionized the diagnosis and treatment of injuries within the hoof wall, enabling the evaluation of soft tissue structures previously unseen with other imaging techniques. Its applications extend beyond the foot, allowing for scanning of the horse’s limb up to the carpus and hock. MRI creates slice-by-slice grayscale images that allow us to see internally into the bones and soft tissue structures (tendons and ligaments). These high-resolution images can reveal structural and physiological changes in the tissues at an early stage of disease, often before they can be identified by other imaging techniques.

in a case of equine septic pedal osteitis

With a Standing MRI, you avoid the risk of general anesthesia. With “down” MRI, imaging can only be done with the horse recumbent (or lying down), and a general anesthetic will always be required. General anesthetic, even in a healthy horse, carries some risk; 1% of horses [1] suffer complications, which can be life-threatening.

MRI is typically the best choice for diagnosing bony and soft tissue disease when more conventional imaging techniques are negative, unclear, or difficult to access. Imaging the limbs while the horse is standing and gently sedated allows internal structures to be assessed while they’re load-bearing.

Standing MRI delivers a definitive diagnosis in over 90% of lameness cases. The use of MRI for diagnosing lameness has significantly increased over the years, with the foot being the most commonly imaged area. This is due to the high occurrence of lameness in this region and the limitations of other imaging techniques in evaluating structures within the hoof capsule. Equine MRI has dramatically advanced our understanding of the disease processes affecting the foot.

What was previously referred to as navicular disease—associated with pain from the heels—can now be differentiated into various pathologies based on inflammation in different anatomical structures in the foot, including the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT), navicular bone, navicular bursa, collateral sesamoidean ligament, and distal impar ligament. Deep digital flexor tendinitis is the most common pathology causing foot pain, and MRI has revolutionized its accurate diagnosis. Within the foot, MRI also allows for a complete evaluation of the collateral ligaments of the coffin joint, whereas previously, only the proximal aspect could be visualized.

However, MRI is not limited to the foot; it also evaluates soft tissue in other areas. While other modalities like ultrasonography can identify lesions in tendons and ligaments distal to the carpus and tarsus, MRI offers more detailed information due to its ability to take slices in multiple directions and utilize different sequences to characterize the severity and activity of lesions.

MRI sequences can detect fluid in soft tissue and bone, which is precious information no other modality can provide, as it is often related to active injuries. MRI excels in visualizing bone, offering insights into structural changes. It is particularly effective in detecting subtle bone abnormalities, including increased bone density (sclerosis) and “bone edema.” Unlike radiographic changes, which often do not correlate with clinical signs, bone edema observed on MRI is typically associated with these signs.

MRI has become an essential part of diagnostic evaluation for lameness. It may serve as a diagnostic aid when other modalities fail to identify the cause of pain clearly and can improve the selection of appropriate therapy and prognosis for injuries in each region.

A case studies library is available here detailing each patient’s history, specific injuries, what scanning with standing MRI found, potential diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Clinical images are included to illustrate the findings and annotated to highlight the area of concern.

Advantages and Limitations of standing MRI

As with every modality available in equine medicine, MRI has advantages and limitations. No single diagnostic method gives us all the answers. Therefore, it’s important to remember that the information provided by any diagnostic imaging technique must be examined in the context of the individual patient.

Advantages

Apart from being an incredibly safe advanced imaging tool, MRI is unmatched in its ability to reveal details in soft tissues. Unlike other modalities, it can ‘see’ through the hoof capsule, providing invaluable information about the foot and revolutionizing the diagnosis of conditions such as navicular disease and DDFT injuries. Although less common nowadays, mainly due to awareness, education, and the use of MRI as the gold standard in diagnosis, a DDFT injury is the most common site of damage in the foot identified by standing MRI scanning of sport horses.

“Hallmarq’s MRI has revolutionized the way foot lameness has been diagnosed in thousands of cases over the last 20 years. Excellent image quality facilitates accurate diagnoses, appropriate treatment selection, and formulation of a prognosis.”

Dr. Sarah Taylor, BVM&S MSc PhD Cert ES(Orth) DipECVS DipECVSMR MRCVS, The University of Edinburgh. The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies

For racehorses in training, fast work at high speeds places the fetlock – particularly the back of the joint – under extreme forces. This repetitive, extreme shock absorption by the joint can lead to traumatic lesions affecting the subchondral bone and/or cartilage. While the lesions can be severe, horses can appear only mildly lame, ‘work out’ of the lameness, or even appear sound but not performing as well as expected.

Radiography typically requires lesions to be significantly progressed before they can be identified. MRI is superior in diagnosing bony injuries, identifying pathology sooner, and potentially preventing more severe or permanent damage while ensuring a prompt and accurate diagnosis.

Limitations

When it comes to the limitations of standing MRI, many cases are related to motion artifacts, considering that it is performed on a standing horse and considers their natural sway. In addition, low-field MRI is not always reliable in detecting cartilage damage, nor can it visualize the keratinized hoof wall. Therefore, solar bruising or foot conformation is unlikely to be assessed accurately.

For some, financial implications may drive the decision-making regarding your horse having a standing MRI scan. Likely associated costs will be:

- Transporting your horse to and from the referral clinic

- The expertise of staff who are specifically trained in MRI scanning

- The cost of sedation for the horse

- Removal of the horse’s shoes pre-scan

- Overnight stabling may be needed: the procedure could require the horse to stay at the hospital for a few days

- A specialist is required to interpret the MRI images, and a radiologist’s report is then written, which may take a few days.

Along with the associated costs, there is also the question of accessibility. For some horse owners, the nearest Standing Equine MRI may be too far to sensibly consider transporting their horse for treatment. For others, however, making that journey is well worth the investment. With a precise diagnosis, you can make the best decision for your horse and agree on a targeted treatment plan to ensure their safe return to work.

Post-Procedure Care

Post-procedure care of equine MRI patients is essential to their recovery, and the advice of your veterinarian should be followed carefully:

- After the MRI scans are complete, your horse will remain at the veterinary practice for careful monitoring until it ‘wakes up’ from sedation.

- Ensuring a return to normal temperature, movement, and gut motility is important

- Food should be slowly reintroduced, and ideally, the patient should pass feces

- Your horse, once ready, can safely return home and – in most cases – on the same day

- Once home, strenuous activity should be avoided for at least the first 24 hours or upon the guidelines provided by the referring veterinarian

- The large number of images obtained during the MRI scan will need to be reviewed and interpreted by an experienced radiologist

- In most cases, a comprehensive report will be produced within 3-5 days, and copies will be sent to you and your referring veterinarian

Comparing Standing MRI to Other Diagnostic Tools

As with all diagnostic imaging technologies, standing MRI has advantages and disadvantages. Here, we look at the practical application of the available modalities most commonly used to aid lameness diagnosis in equine practice. Each has its unique benefits, and deciding which to use depends on various factors, including the type of issue, cost, and the details each imaging method can capture.

Radiography (X-ray)

X-ray is often the primary method of assessing bone condition. It is inexpensive and can frequently be used without bringing the horse into the clinic (ambulatory). However, its main limitation is that the two-dimensional images produced show shadows of overlying bones (superimposition). Even with multiple different projections, it is sometimes difficult to evaluate areas where multiple bones overlap. Another limitation of X-rays is that they don’t provide information regarding the surrounding soft tissue. For example, a horse might be diagnosed with a fracture of the wing of the pedal bone via X-ray. These fractures usually have a good prognosis, but the horse doesn’t respond to conservative treatment as expected. However, an MRI might reveal that nearby soft tissue structures (such as the collateral ligaments) have also been affected.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is widely used to image soft tissues in human and veterinary medicine. It’s a relatively cheap technique, but the grainy images can be challenging to interpret and rely heavily on the operator’s skill. Ultrasound waves will not pass through bone, so only the periphery will be assessed. However, it is beneficial for determining essential structures in the foot due to the keratinized hoof wall, frog, and sole. While ultrasonography allows a dynamic evaluation of the soft tissue structures, standing MRI gives more detailed information on the tendons and ligaments. Seeing slices taken in multiple directions allows a complete evaluation of the area, and different sequences enable differentiation of chronic and acute soft tissue injuries.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT scans use X-rays and computer processing to create cross-sectional images of the body. CTs are highly effective for imaging bone and mineralized tissue and detecting fractures. The CT scanner rotates around the patient, capturing multiple photos of the area of interest from different angles. These images are then used to build a detailed 3D reconstruction of the internal structures. CT scans are faster than MRI; once the patient is positioned, it will only take 2-5 minutes to acquire an image. This speed is a key benefit of its technology, particularly in emergencies. Although soft tissue visualization with CT improves, MRI remains the modality of choice for diagnosing soft tissue injuries. While CT is superior for imaging bone, it cannot detect bone edema, which MRI can.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

“MRI is an advanced imaging modality that provides a 3D view of soft tissue and bone structures, offering significant advantages over X-rays and ultrasound. Unlike radiographs, which require a 30-50% change in bone density to detect lesions, MRI can identify early-stage structural changes like bone edema and sclerosis. For soft tissue, MRI detects subtle changes in ligaments and tendons that may be missed on ultrasound. Even when lesions are visible with ultrasound, MRI offers more detailed information by capturing images in multiple directions and using various sequences to assess the severity and activity of lesions more precisely.”

“Standing MRI allows us to accurately diagnose the cause of lameness in the vast majority of cases where standard diagnostic techniques fail to give us the answer. It permits the selection of appropriate treatment methods, whereas, without it, we would often have been guessing.”

Tim Mair, BVSc, PhD, DEIM, DESTS, DipECEIM, MRCVS, Bell Equine Veterinary Hospital, Kent, UK

The Future of Equine MRI

The use of MRI in Orthopaedic imaging has been a reliable modality for many years. As with any modality, the ultimate goal of low-field MRI – when used in equine practice – is to aid effective lameness diagnoses. Increased knowledge and image acquisition techniques continue to grow as specialists in the field of equine lameness diagnosis look for new and improved ways of benefiting the patient.

With the image quality key, software enhancements that minimize artifacts and allow for the horse’s natural sway continue to be developed. The field of veterinary diagnostic imaging is undergoing significant transformation with the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. Their application benefits reduced scan times and improved image quality. For the equine patient, reduced scan times mean less time spent under sedation and a quicker return to health.

Conclusion

Key findings:

- MRI is cost-effective and has a unique ability to identify both soft tissue and bone pathology, providing highly detailed images of each

- sMRI is the gold standard for soft tissue imaging on standing horses

- MRI allows detailed cross-sectional imaging of targeted structures, with multiple planes oriented in different directions to create 3D images, avoiding the superimposition of surrounding structures

- MRI does not use ionizing radiation, reducing the biological hazards associated with its use compared with that of radiography or computed tomography

- MRI can detect bone edema, which is often considered to represent “active” changes in the bone. X-rays, ultrasound, and CT do not have this ability

“Our MRI unit offers significant benefits over our previous imaging capabilities, such as radiographs and ultrasound. It offers the highest soft tissue imaging detail possible and unlocks certain diagnoses for us now that were never possible previously. This enables us to make the most accurate diagnosis for our equine patients and means our treatment plans can be more specific and targeted. Since installing Standing Equine MRI at our practice, we have been able to offer a higher standard of care to horses who come to see us”

Andrew Jones, Clinical Director, and Surgeon CVS Endell Equine Hospital, UK

Hallmarq is proud to be pushing the boundaries of what can be achieved with advanced diagnostic imaging. Our Standing Equine MRI machine enables imaging of the distal limb without the need for general anesthesia. This has improved safety for horses, made advanced imaging more affordable and accessible to owners, and increased the number of horses that can undergo advanced imaging. All this combines to increase patient welfare and veterinary knowledge.

FAQ’s

What is a Standing Equine MRI Scan?

Standing Equine MRI is one of veterinary medicine’s most valuable non-invasive diagnostics.

How Does the Standing Equine MRI Work?

The standing equine MRI uses a specialized magnet and imaging system designed to accommodate a horse’s lower limbs while the animal remains standing and awake, eliminating the need for general anesthesia. It captures detailed cross-sectional images of bones, joints, and soft tissues by creating a strong magnetic field and using radio waves to generate high-resolution images, allowing veterinarians to diagnose conditions without invasive procedures.

Why Would my Horse Need an MRI?

Your horse might need an MRI to diagnose conditions that are difficult to detect with other imaging methods like X-rays or ultrasounds, such as soft tissue injuries, subtle bone fractures, or joint issues. MRI is particularly useful for identifying problems in the horse’s hooves, tendons, ligaments, and joints, helping to pinpoint the cause of lameness or discomfort when other diagnostic tools are inconclusive.

Is a Standing MRI Safe for my Horse?

Yes, a standing MRI is generally safe for your horse. It is a non-invasive procedure that does not require general anesthesia, reducing the risks associated with sedation and allowing the horse to remain calm and comfortable.

[1] Morgan, Jessica M., Helen Aceto, Timothy Manzi, and Elizabeth J. Davidson. ‘Incidence and Risk Factors for Complications Associated with Equine General Anaesthesia for Elective MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING’. Equine Veterinary Journal, 7 November 2023, evj.14026. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.14026.