Both down and standing MRI play important roles in equine diagnostics, but they differ in image quality, patient safety, and practical considerations. Each has its own advantages depending on the clinical scenario and level of detail required for diagnosis. Chrysanthi Pitaouli walks us through the pros and cons of each modality.

Just like humans who regularly turn to Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in the care and assessment of soft-tissue and bony injury, horses are frequently referred for advanced imaging such as MRI, which provides superior detail in evaluating soft tissue and osseous structures associated with lameness. In equine medicine, MRI is widely regarded as the gold standard for imaging the foot, yet its utility is not limited to the hoof. We frequently scan higher up the limb, reaching the fetlock, carpus, tarsus and stifle.

As MRI gained recognition for its value in equine lameness investigation and demand increased. Hallmarq Veterinary Imaging pioneered their innovative Standing Equine MRI machine, designed specifically for the standing sedated horse. The alternative option is recumbent or ‘down’ MRI which requires the horse to be anaesthetised.

The importance of image quality in MRI imaging

In equine imaging, magnetic field strength is central to image quality. MRI systems may be classified:

- High-field (typically 1.5T–3T)

- Low-field (0.2T–0.3T)

A higher magnetic field strength typically delivers finer image detail and greater resolution. Recumbent or “down” MRI can use either high-field or low-field magnets. Standing Equine MRI – developed by Hallmarq specifically for the sedated, standing horse, uses a low-field system. As the patient remains standing, the risks and costs of anaesthesia are avoided. Widely regarded as the gold standard for imaging the equine foot in standing horses, standing MRI provides excellent diagnostic value.

Motion artefact has been a critical factor in achieving diagnostic image quality in standing systems. As motion correction technology continues to evolve, more recent innovations such as Hallmarq’s iNAV, combined with optimized sedation protocols, deliver markedly improved image quality higher up the limb. Important research has show that, when imaging the equine foot, image quality is not affected by whether the horse is standing or recumbent, but more by the acquisition system itself [1].

MRI and motion correction technology

Image quality in standing MRI has improved dramatically over the years. Hallmarq’s award-winning motion correction software automatically compensates for natural patient sway, and more recent developments have significantly reduced scan times compared to when standing MRI was first introduced.

iNAV is the latest enhancement to Hallmarq’s motion correction software and uniquely designed to address one of the most persistent challenges in veterinary imaging: patient movement.

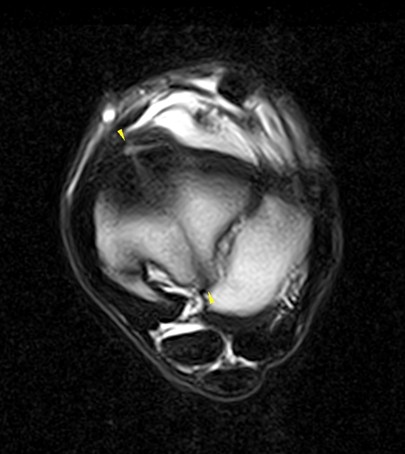

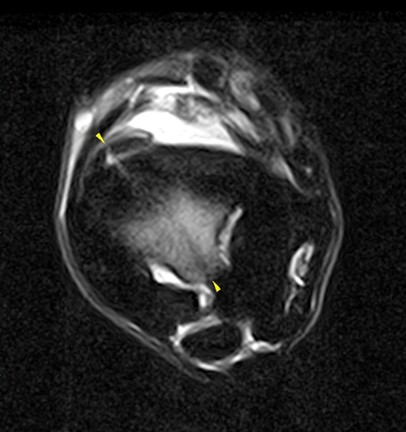

In a recent case study highlighting abnormal sclerosis of the central tarsal bone, diagnostic scans of difficult to image areas were possible with iNAV which proves particularly beneficial when imaging the fetlock, tarsus, carpus, or high suspensory. The improved detail and the clarity it delivers is invaluable for accurate assessment.

Standing MRI has considerably improved our assessment of lameness cases. In addition, the introduction of iNAV allows us to obtain images of exceptional diagnostic quality even for difficult areas, such as the tarsal region. In the present case, the fracture line and the area of bone oedema-like signal are clearly defined with minimal motion artifacts, which would not have been possible otherwise.”

Dr Claudia Fraschetto DMV, DECVSMR, ISELP Cert, Clinique de Grosbois, France.

Although certain fine details may only be visible on high-field systems, studies confirm that the vast majority of everyday lameness-related conditions can be effectively diagnosed with low-field standing MRI [1-6]. Moreover, standing MRI has proven invaluable beyond the foot and fetlock, providing crucial diagnostic information regarding pathology affecting the proximal suspensory region, carpus, and tarsus [7].

What’s the risk of MRI imaging?

Down MRI requires the horse to undergo general anaesthesia (GA) before image acquisition. Once anaesthetised, the recumbent horse is positioned for scanning, with the distal limbs placed into the machine’s tubular core. High-field MRI cannot be performed on awake horses, as even the smallest movement creates motion artefact that renders the images non-diagnostic, leaving general anaesthesia as the only option.

Standing low-field MRI produces the same image resolution as recumbent low-field MRI without relying on general anaesthesia (GA) to reduce motion artefact.

Despite the proficiency of practice staff in administering anaesthesia and obtaining detailed images, many owners remain sceptical regarding the potential risks associated with down MRI.

Reducing the risk to the patient

General anaesthesia always carries risk, even in healthy horses. A large retrospective study reported that around one in 100 horses experience a peri-anaesthetic complication [8]. In more recent research looking specifically at MRI, the risks are equally clear: Manning & Sampson (2025) found that peri-anaesthetic complications occurred in a substantial number of cases during high-field MRI, reinforcing the challenges of performing these procedures under general anaesthesia. Similarly, Morgan et al. (2024) identified both the incidence and risk factors for complications associated with anaesthesia for elective MRI, underlining that even in controlled, elective settings, adverse events remain a genuine concern. For owners and trainers of elite sport horses, this risk versus benefit calculation is a difficult one and, for many, it is simply not worth taking.

When investigating lameness, the choice of imaging modality depends on balancing the level of diagnostic detail required with the risk to the patient. MRI is usually considered after lameness examination, diagnostic nerve blocks, and initial imaging with radiography and ultrasound suggest pathology that cannot be fully characterised with these techniques. Standing MRI, requiring only mild sedation, often represents the safest and most practical first step, providing detailed information for most distal limb conditions. In cases where the standing study does not fully explain the clinical signs, or when extremely fine anatomical detail is needed, referral for high-field MRI under general anaesthesia may still be warranted.

Cost implications of MRI scans

Down MRI undoubtedly places a larger demand on practice staff. Highly skilled personnel are needed to administer anaesthesia, and several people are required to ensure the safe positioning of the horse in the magnet. The patient will need constant monitoring for the duration of the scan process. These additional costs are, of course, passed on to the horse owner.

In comparison, standing MRI can be operated by just two staff – one qualified by Hallmarq to operate the machine and one to manage the patient. Since standing MRI does not require general anaesthesia, image acquisition is complete in a matter of hours as opposed to the lengthier procedure that down MRI demands. The practice and horse owner benefit from associated cost savings and most veterinarians can see more patients in less time, thus generating more revenue.

For the veterinary practice, Standing Equine MRI costs less to install, requires less space and needs less shielding than high-field MRI. The stronger the magnet, the more care is needed in planning the surrounding area to minimise interference with image quality.

Down MRI requires a large, dedicated room taking up valuable clinic space. In comparison, Hallmarq’s Standing Equine MRI can be delivered in a self-contained modular room and dropped into place for quick and easy setup. The patient is simply walked into the magnet, a hoof coil attached to the relevant limb and scanning can start. Overall, it’s a much less labour intensive process than that required by down MRI.

Down vs. standing equine MRI: what’s the answer?

As with all clinical decisions, there is no single answer that fits every case. The key consideration is the level of detail required for diagnosis. Evidence suggests that field strength and the acquisition system itself are more critical determinants of image quality than whether a horse is scanned standing or recumbent [1]. Ultimately, the question becomes whether a high-field system is necessary to capture the finest anatomical detail, or whether a low-field standing system provides sufficient information to make the diagnosis safely and effectively.

High-field systems can deliver finer anatomical detail, but for the majority of everyday lameness cases, low-field MRI – particularly Hallmarq’s standing system – provides the necessary diagnostic information safely and effectively. When combined with the advantages of avoiding general anaesthesia and reducing overall costs, standing MRI represents a practical and sensible first step in most equine lameness investigations.

References

- [1] Byrne, C.A., Marshall, J.F., Voute, L.C. (2020) Clinical magnetic resonance image quality of the equine foot is significantly influenced by acquisition system. Equine Vet J. 00, pp 1– 12

- [2] Powell, S.E., 2012. Low‐field standing magnetic resonance imaging findings of the metacarpo/metatarsophalangeal joint of racing Thoroughbreds with lameness localised to the region: a retrospective study of 131 horses. Equine veterinary journal, 44(2), pp.169-177.

- [3] Murray, R.C., Mair, T.S., Sherlock, C.E. and Blunden, A.S., 2009. Comparison of high‐field and low‐field magnetic resonance images of cadaver limbs of horses. Veterinary Record, 165(10), pp.281-288.

- [4] Werpy, N.M., 2007. Magnetic resonance imaging of the equine patient: a comparison of high-and low-field systems. Clinical techniques in equine practice, 6(1), pp.37-45.

- [5] Porter, E.G. and Werpy, N.M., 2014. New concepts in standing advanced diagnostic equine imaging. Veterinary Clinics: Equine Practice, 30(1), pp.239-268.

- [6] Sherlock, C.E., Mair, T.S., Ireland, J. and Blunden, T., 2015. Do low field magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities correlate with macroscopical and histological changes within the equine deep digital flexor tendon?. Research in veterinary science, 98, pp.92-97.

- [7] Labens, R., Schramme, M.C., Murray, R.C. and Bolas, N., 2020. Standing low‐field MRI of the equine proximal metacarpal/metatarsal region is considered useful for diagnosing primary bone pathology and makes a positive contribution to case management: a prospective survey study. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, 61(2), pp.197-205.

- [8] Dugdale A.H., Obhrai. J., Cripps P.J. (2016) Twenty years later: a single-centre, repeat retrospective analysis of equine perioperative mortality and investigation of recovery quality. Vet Anaesth Analg. 43, (2), 171-8

- [9] Manning, H. and Sampson, S., 2025. Peri‐anaesthetic complications in 1798 equids undergoing high‐field elective orthopaedic MRI at a tertiary referral hospital. Equine Veterinary Journal, 57(3), pp.666-673.

- [10] Morgan, J.M., Aceto, H., Manzi, T. and Davidson, E.J., 2024. Incidence and risk factors for complications associated with equine general anaesthesia for elective magnetic resonance imaging. Equine Veterinary Journal, 56(5), pp.944-951.